Tucked away down Press Bay Alley in downtown Ithaca, at the bottom of some stairs, behind two sets of heavy doors, a group of students is gathered. The room is decorated in a dad’s-garage-meets-mad-scientist’s-lab sort of aesthetic — a flashing grid of Ping-Pong–ball lights dance in one corner opposite a bright arcade game. The walls are covered in tools. Nearly every horizontal surface is cluttered with wood or metal. The sharp scent of sawdust stings the air. The only external betrayal that this is an organized space, and not simply an eccentric’s workshop, is a bright yellow sign over the first set of doors. There’s no writing on it, simply the print of a smiling cartoonish robot face.

This is the first indication that the building houses the Ithaca Generator, a makerspace and collective that offers makers of all backgrounds the space, tools and community to create. At its core, a makerspace is a place for making things. Nearly every major city has one or multiple makerspaces now. Creators come in to make anything from phone applications to furniture to robots. If you can do it yourself, you can make it in a makerspace. The Ithaca Generator’s makerspace offers members an opportunity to use tools like 3-D printers and laser cutters and saws, and also brings together a community of people that can collaborate.

Anyone can come to makerspace open hours, held periodically every month, but in order to fully utilize IG resources, makers have to become members and pay dues. There’s a tiered payment system depending on the type of materials the member would like to use, and student discounts are offered.

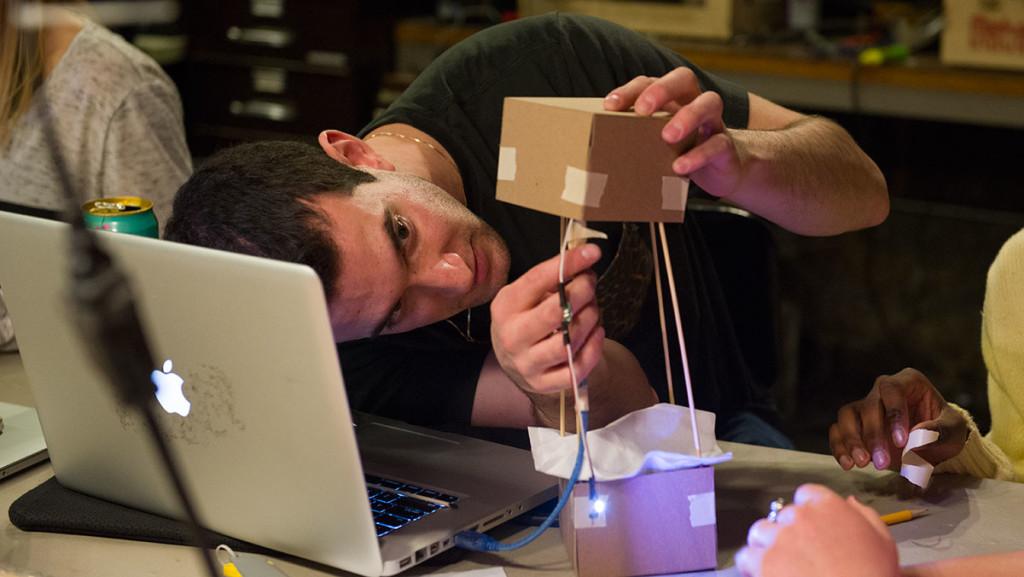

Every day brings forth a new cluster of projects. On this particular day, Feb. 10, Ithaca College students in Xanthe Matychak’s Make Better Stuff Studio class are making laser–cut boxes. They trace each wall with the laser cutter, which reads a drawing from the computer and then burns jigsaw-edges into the thin wood.

“If anything starts to catch fire … take it out and stomp it,” Matychak cautions her students.

The wood pieces are transferred from the laser cutter to a worktable, where students use thick Titebond II glue to fit the five pieces together. It sounds simple, but the sides don’t stay up very well on their own, and a few students struggle to keep the pieces from toppling as they dry. In the end, though, the boxes are assembled without much incident, and class is dismissed.

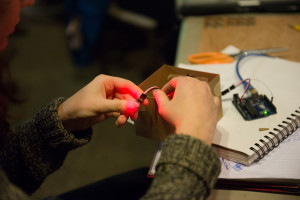

This class is a pilot course in environmental science. Matychak, a lecturer in the Department of Environmental Studies and Science, said the first weeks of classes were focused on sustainable design principles: making stuff that is both sustainable and utilitarian. Now the students are moving on to their first project: light boxes that will be presented at Ed Tech Day on March 24. In addition to the laser cutter, the students will be using Arduinos, small computers that control physical movements, to program the lights.

She pulls an Arduino out of one of the many drawers lining the walls. It’s tiny, about the size of the palm of a hand, dotted with an organized and awfully technical–looking grid of electronics.

“I don’t have a background in electronics. I’m not an Arduino master, but I can make lights do things, and I can make motors do simple things,” Matychak said. “I pretty much cut and paste, and that’s what I’m going to teach them how to do. In the simplest way, it makes stuff do stuff.

Matychak said it’s very common for members of makerspaces to share materials among one another. She gestures to a laser cut wood Millennium Falcon hanging from the ceiling. It, along with a few laser cut TIE fighters, were created from a shared template posted online.

“Part of this culture is that people share stuff, so they make computer code for different things and post them online for free,” she said. “You can grab it and use it straight up and manipulate it, or whatever you want. ”

Creating sustainable objects is of particular interest to Matychak, whose background is in industrial and product design with a focus on sustainability. She said she wants her class to introduce students to desktop manufacturing, using software like 3-D printers to create objects, a new tool she says IG is at the cutting edge of.

“So just like desktop publishing in the ’80s, where people could all of a sudden layout their own newspapers and books and print them, we can now do that with physical products,” Matychak said. “What happened is the cost of that technology has dropped to the floor, and the ease of use is coming up.”

The first imaginings of IG were actually in the ’90s at the cusp of another technological revolution: the Internet. Matychak said founding president Mark Zifchock and his friends used to get together and mess around on the Internet, which was becoming more available to the average tech geek.

“They would just play with it and were like, ‘This is going to be huge one day. I can feel that this is going to be really important,’ and so they just got together every week and messed around with it,” Matychak said.

Zifchock said these meetings were also the seed of one of IG’s founding principles, that people can and should make their own things. In the early ’90s, he said, he and his friends were deeply into the punk rock scene of the late ’80s and ’90s. It was a community where doing it yourself was emphasized, both out of necessity — it’s hard to find pants with zippers and safety pins all over them in Ithaca — and interest in taking products and transforming them.

“You had to sew your own punk–rock clothes and make your own stuff, and we created our own notion of it — our own culture of it,” Zifchock said. “It’s really empowering to say that I’m making my own stuff, it’s my stuff, I made it, nobody commercially created this for me. It had all of the wonderful sort of sensibilities and imperfections of things that are handmade.”

This ethic of transforming commercialized objects, he said, informed one of the guiding principles of IG, which he; his wife, Claire; and a few friends established in 2012.

“It was really important to us that we reveal to people that they can create stuff themselves, and the thing they create has a value intrinsically because you created it and you got it there,” he said.

This idea spoke to Aaron Zufall, a sophomore at the college who joined IG his freshman year. Now Zufall is on the board, and he said he usually uses the space to create small objects to make his life easier.

“I like woodworking, I’m not great at it, but sometimes I’ll come down here,” Zufall said. “When I showed up at my dorm this year, the wardrobe I had only had half a coatrack, and so I just came down here on the first day of school and built another coat rack for the other side of the dorm because I couldn’t fit everything.”

However, he said, myriad large projects are simultaneously being created at IG. One member is working on building a boat. Another is building a solar-powered bike rack. There are members who specialize in areas such as electronics, programming and woodworking, and different members will often collaborate to produce one project. Zifchock echoed this idea. He said one of his favorite projects was a go-kart created by Claire and a few other IG members. The go-kart, which was built using a child’s Power Wheels car and shaped like a green dragon, was raced at a Maker Faire in New York City and won some awards.

“It was cool. It was great,” he said. “My wife had never welded before, and she was gleeful to have sparks flying. It was pretty exciting. They raced around, and they were repairing it in the pit and everything. We had a lot of kids who were helping out with it. … They were there cheering us on. I think it was a really successful project in a lot of ways.”

Zufall said he is the only IG member who is a student at the college. As a board member, he’s working on changing that and attempting to add to the diversity of the Generator. There are currently about 48 members, but only 30 percent of the members are women. This is perhaps a high number when compared to other makerspaces, but both Matychak and Zufall want to increase that number to closer to 50 percent. Matychak said she thinks the first step is adding more women to the board, which currently has a female president.

“Diversified leadership leads to diversified membership. … You can’t be what you can’t see,” she said.

One strategy Zifchock is working on to increase general membership takes the form of a little robot. The idea is that he will build a robot that can be controlled using a phone application. The robot will roll around town and interact with people, drumming up more attention for the Generator and, in doing so, add members. So far, the robot is still in the first stages of development. The robot’s body is a potbellied Honeywell air filter with two wheels. Zifchock opens it to reveal a nest of wires and Arduinos. He’s not sure when it will be done — he has a few other projects that are more in demand of his attention — but he’s got big ideas for it. He wants to add googley eyes and a tongue around the handle to make it more anthropomorphic and engaging.

“The idea with the robot was that there would be a companion also, so we have a big robot and a little robot. … The operator can imbue it with a sort of individuality and spirit that people really like,” he said. “I think that if we had two robots — a little one and a big one — I think people would go nuts. You could do all sorts of hilarious and fun things with it. I think it’s a great way to show people what we’re about.”

Zifchock said it’s important to him to make sure technology is used in a way that benefits humans, like the robot. Beyond being cute, this robot has a purpose: to benefit the makerspace and the people within. Technology is powerful, he said, and the Generator tries to use it to human advantage.

“It was a question we had to ask ourselves again and again. … It’s something that I’d like to continue to talk about as a makerspace: How is technology serving people, human beings, in an egalitarian way?” Zifchock said. “Because to ignore that, we can pursue efficiencies that don’t serve humans, or serve them unequally. We can create a world that doesn’t look like anything we’d like to imagine.”