This year’s presidential campaign between Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and Republican nominee Donald Trump has been characterized more by personality than policy.

Among the policy discussions, higher education has been less prominent than a handful of other topics, including immigration, national security and trade. However lesser-known the proposals, their potential impact on private colleges could be significant.

Clinton has released a plan calling for free tuition at public colleges in their home states for students with a family income below $125,000. Economists predict such a plan could reduce enrollment at private institutions and could affect Ithaca College.

Trump has remained vague about his higher education plan. He has spoken of income-based repayment plans for student loans, and of requiring colleges with large endowments to annually use their returns on endowment investments to lower tuition costs, an idea U.S. Rep. Tom Reed, whose district encompasses Ithaca, has championed. However, the college’s endowment is not large enough to fall into this category.

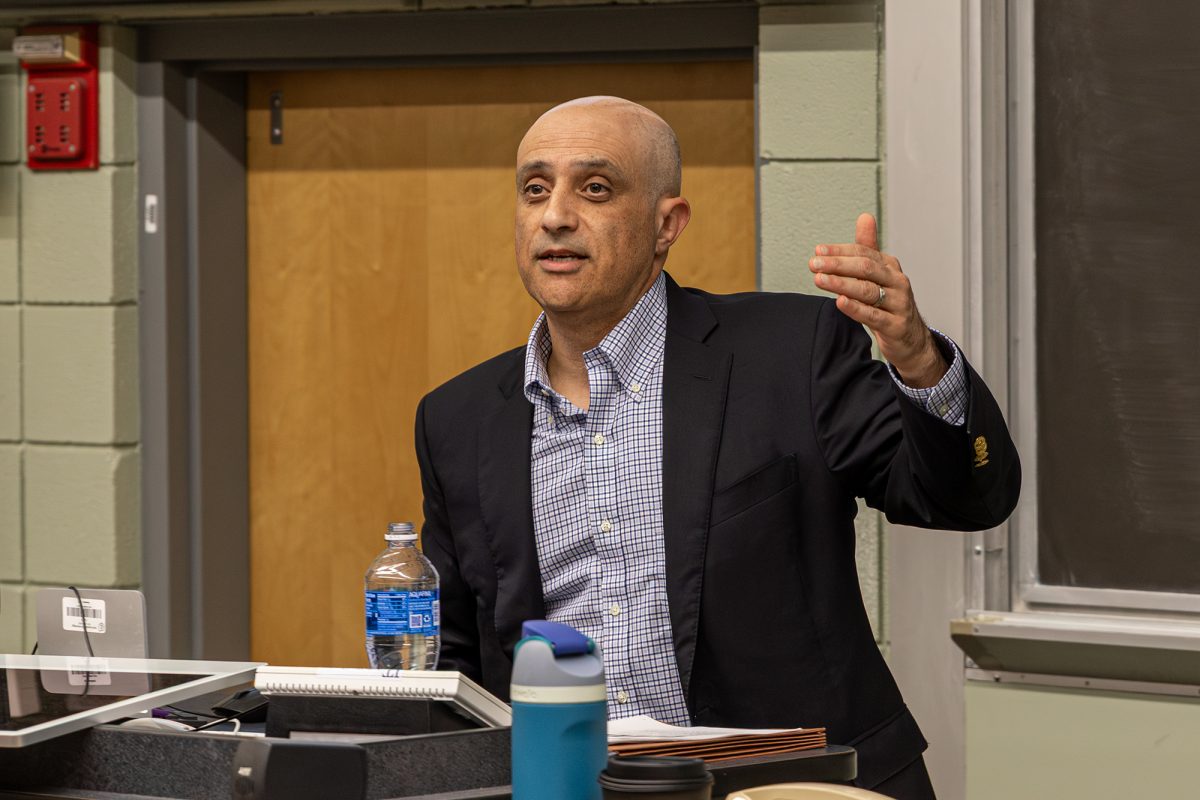

“The magnitude of … debt is getting people’s attention,” said Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. “And there’s frustration from policy makers and the public, that they keep putting more money into higher education, and tuition and fees keep rising.”

CLINTON’S PLAN

Clinton’s plan calls for free tuition for students with a family income up to $125,000 at their home state’s public colleges by 2021. The plan would immediately go into effect for students whose family income is below $85,000.

She is also calling for free tuition at community colleges, more child support services for students who are parents and the creation of a $25 billion fund to support historically black colleges and universities and other minority-focused institutions. The plan calls for a three-month moratorium on loan payments for all federal student-loan borrowers. It also would provide aid for borrowers in refinancing loans, and it would lower interest rates on loans.

Clinton’s campaign estimates that her plan would cost $500 billion over a decade and would be paid for by eliminating tax loopholes for the rich, such as adding limits on deductions . It would greatly increase the federal government’s role in funding higher education, said Sandy Baum, who has advised the Clinton campaign and is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, a liberal-leaning think tank.

“The goal from the beginning, and the continuing goal, is to make sure that students from all backgrounds can afford to go to college — that they don’t accumulate excessive debt in doing that,” Baum said.

States have been cutting higher education spending, Baum said, and Clinton’s plan calls for the federal government to intervene and reverse that divestment. States would also be expected to increase their contributions to higher education.

The plan has been criticized from the right. Neal McCluskey, director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, said it would lead to “monstrous unintended consequences that the help is actually hurting.” He said it would drastically increase the number of students at public colleges and universities, which could hurt the quality of those institutions, and would exacerbate the problem of students’ starting college but not completing their degrees.

Kelchen said the price tag of the proposals will keep increasing as costs of higher education continue to increase. He said he thinks the proposal does not represent a long-term solution and that colleges need to bring down the cost of higher education to address the issue.

“The problem is it’s much easier to promise to essentially throw money at the problem than try to fix the root problem,” he said. “Particularly when some of the solutions might mean things like faculty teaching more classes, not spending as much on facilities, factors that may not make students or faculty happy in an election year.”

SANDERS’ INFLUENCE

During Clinton’s primary campaign against Sanders, she campaigned with a plan calling for “debt-free” college education. Under Clinton’s debt-free plan, students whose families could afford to pay the cost of tuition would pay it, Baum said. Those who could not would get the rest of their tuition covered by Pell Grant funding and 10 hours a week of student employment.

Sanders, on the other hand, called for free tuition at public institutions for all students. The Sanders campaign said it would have paid for the $75-billion-a-year plan by increasing taxes on Wall Street.

Free tuition for all, such as Sanders’ plan, would lead to large tax increases across the board, Baum said. The funds from these increases would primarily benefit students from affluent families as those students are more likely to go to college, go to expensive colleges and stay in college for a longer time, she said.

“The idea that the primary use of taxpayer dollars should make sure that people from rich families don’t have to pay for the education that will ensure they stay rich … that’s not progressive,” Baum said.

Clinton announced the shift in her plan to free tuition to students with a family income up to $125,000 just before this summer’s Democratic National Convention.

“It’s a much more extensive plan than her previous plan, and it covers more students and covers more of the full cost of education, though not all,” Kelchen said. “It’s really a nod to what Bernie Sanders pushed for in his presidential campaign.”

Heather Gautney, associate professor of sociology at Fordham University, was a senior researcher for the Sanders campaign and the co-founder of the Higher Ed for Bernie initiative. The Sanders campaign’s concern over the ties between Wall Street and higher education encouraged them to call for the more radical approach to tuition-free higher education, she said.

“That idea would really solve the accessibility problem right away,” she said. “An idea like that only fits if you look at the large social model, and during his campaign, he would mention places like Denmark and Finland … where the understanding is there is a basic set of social safety nets and social welfare, and public institutions sort of address the basic needs of the population … and putting higher education into that mix.”

Between the end of the primary and the convention, the Clinton and Sanders campaigns negotiated a compromise on the issue of higher education, calculating the $125,000 threshold. Gautney was “not in the room,” but “near the room” during these negotiations.

“That dollar amount had sort of gone up and down between the campaigns until they reached a place where the senator believed that that would be an extraordinary number of people, practically 80 percent of the population,” she said.

However, the compromise has led to criticism from some on the left for creating a “means test” for higher education, and Gautney said she was “really unhappy” with the compromise. She said setting a dollar threshold during the campaign would only lead to that number’s getting lowered during negotiations in Congress.

“My suspicion is that $125,000 will be lowered and lowered and lowered to the point where it won’t be 80 percent of the population; it will be a much smaller percentage of the population,” she said.

IMPACT OF CLINTON’S PLAN ON PRIVATE INSTITUTIONS

Clinton’s current plan could increase enrollment at public two- and four-year institutions by 9–22 percent, a study from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found. Up to 15 percent of that could come from private institutions, according to the study.

The center’s best guess, or median, for the increase in enrollment at public colleges is 16 percent, said Cary Lou, senior analyst at the center. Seven to 15 percent, with a median of 11 percent, would come from students leaving private colleges and universities, while the rest of the increase would come from new students who would not have otherwise gone to college.

Lou said “there’s a good chance” Ithaca College would be affected if Clinton’s plan were enacted.

“At least some of the students who are more price-sensitive would take a look at the increased difference in price between the private and public sector, and might chose to try to get into a public institution, and if they did, would go to the lower-cost option,” he said.

The plan may also have an unintended impact on minority students and students from a lower financial class, Lou said. The study raised concerns that some well-qualified minority students may be squeezed out of more selective public institutions by students transferring over from the private sector.

“On the private side, we’re concerned that the fact the change may impact price-sensitive students the most might have a negative impact or could decrease diversity at some private institutions as well,” he said. “It’s something that, if a policy like this were to be put into place, that institutions just need to be mindful of and consider and keep in mind as part of the admissions, applications, recruiting process.”

Presidents at other small private colleges have expressed concerns about how the plan would impact their institutions and the students they serve.

“It’s impossible for a small private college to compete with $300 billion (sic) going to public universities,” said Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University in Washington, D.C. “This just would tilt the playing field so hard that it really could kill a lot of small private colleges.”

Kelchen said he did not think Ithaca College would see a large impact since the college is “relatively selective” and because the public State University of New York system is already “very inexpensive” compared to the cost of public institutions in other states. For example, tuition in the SUNY system is $6,470 a year, while at Rutgers University, the largest public institution of New Jersey, tuition is almost double that, at $11,408.

“It would affect private colleges in states that have higher tuition in the public sector, and it would really affect colleges that are admitting almost every student who applies,” he said.

Sophomore Abriana Smith applied to Rutgers in her home state of New Jersey but decided the college was a better choice for her.

“It was definitely a tough choice, financially,” she said. “Obviously Ithaca was a lot more for me. I had to weigh it out, but I really liked Ithaca, and I thought it would put me in a better career position, so I hope it will pay off.”

However, Smith, who is planning on voting for Clinton, said if tuition at Rutgers were free, that would have swayed her decision. She said she supports Clinton’s plan.

Freshman Alexander May, on the other hand, did not apply to the public colleges in his home state of Massachusetts. He said he decided to go to the college because of the educational quality, and he said he still probably would have come to the college if the public option were free.

“It was a pretty good program for what I wanted, and it’s nice here,” he said.

President Tom Rochon declined to comment.

Gerard Turbide, vice president for enrollment management, said it was difficult to predict what impact such a plan would have on the college. The passage of this plan would “change the landscape” of higher education, but it is unclear how, he said.

“Everything gets at individuals looking at the comparative cost and value, and the return on that investment,” he said. “I don’t want to say that it will put more pressure on institutions to distinguish themselves or kind of communicate what that value is because I think that’s already pretty much at a steady high level of importance for us.”

Data on how many students at the college would fall under the $125,000 threshold is not publicly available, and Turbide said it would not be made available.

TRUMP’S PLAN

Republican nominee Donald Trump has not made higher education affordability a major focus of his campaign.

Trump’s most thorough address on higher education so far during the campaign came Oct. 13, when he proposed a rate of income-based repayment for student loans capped at 12.5 percent of a borrower’s income with all debt forgiven after 15 years. He said he would reduce federal regulations on colleges and universities, which he said would decrease student costs as institutions would have to spend less to comply.

Kelchen said due to the absence of details, Trump’s ideas don’t represent a plan, although they could if the campaign fleshes out the ideas a little more.

Trump also spoke out against “political correctness” on college campuses, and also spoke on a topic he has made a central tenet of his discussion of higher education: endowments.

During a Sept. 23 speech, he said he would encourage Congress to make institutions with large endowments help lower student cost or risk losing their tax-exempt status.

This idea has been championed in Congress by Rep. Tom Reed, a Republican who represents Ithaca. He has written legislation to target schools with endowments over $1 billion. This legislation would require those schools to use 25 percent of their annual endowment income as financial aid for students.

“To me, that is only appropriate, to have a direction of those monies for what the public purpose that these institutions get their not-for-profit status for, to educate our kids,” he said.

As of 2015, Ithaca College has an endowment of $289.3 million, well below the $1 billion threshold for endowments that would be impacted by Reed’s legislation.

At the college, returns generated from investments in the restricted endowment funds are used according to the donor’s wishes, and returns from unrestricted endowment funds are used “throughout the budget, including for financial aid, faculty and staff salaries, classroom and laboratory equipment, and a host of other expenses incurred in operating the college,” said Janet Williams, interim vice president for finance and administration, via email.

Since the majority of college endowment funds are restricted, finding enough available funds to make a difference in student price would be a challenge, Kelchen said.

“Another concern is that if donors knew that some of their funds would be used for a purpose they didn’t want, they might stop giving altogether, making the problem worse,” Kelchen said.

Only 92 U.S. colleges and universities had endowments valued at or over $1 billion in 2015, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. Just 92 would fall under Reed’s plan, This representing only a small portion of the thousands of higher education institutions in the United States.

“It won’t do much to help improve college affordability because so few colleges have large endowments and because a good number of these colleges already have fairly generous grant programs for financially needy students,” Kelchen said.

Though using endowments to limit student costs is a politically popular idea on the right, McCluskey said it does little to address the fundamental problems in higher education.

Reed said the endowment portion is just the first step and is not the “magic bullet” to solve the crisis.

Since most institutions have nonprofit status, he said, he is working on putting together a blueprint requiring more disclosure for institutions on their spending, requiring them to create a college cost containment strategy that they would adhere to.

“I think it’s only fair that we use the endowment, the not-for-profit space, as the tool to put more spotlight on this area and really drive these costs down by asking the hard questions of those setting these prices,” he said.

WHAT COULD GET DONE

Most of the advances in addressing higher education issues in the foreseeable future will come from the state level or federal executive branch, Kelchen said, due to congressional deadlock.

“If they can do things by executive order, or through the executive branch, that’s the things that will get done,” he said. “Otherwise, none of the ideas proposed really seem to have strong bipartisan consensus.”

For example, President Barack Obama’s fight against for-profit colleges was primarily done from the executive branch. Another reform that is picking up speed is tuition-free community colleges. Tuition-free community college proposals have been passed in several states. Such a proposal passed with bipartisan support in Tennessee, and 30 similar programs have begun across the country.

“Even if the action isn’t at the federal level, you’ll see states trying new and different things,” Kelchen said.

Reed was more optimistic about bipartisan gains in Congress and said next year offers an opportunity.

“With the new administration — and both the Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton campaigns talking about college costs — I think there’s a big window of opportunity for us to address this,” he said.