Ithaca College senior Elizabeth Cady, a resident assistant in East Tower, said this semester she has had to respond to two mental health–related calls. Both times, she said she had to call the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management.

“Those situations were both pretty similar in that [Public Safety officers] showed up and were loud and very heavy-handed when interacting with the residents who were going through a mental health crisis,” she said.

Cady said the on-duty residence director is usually also involved in responding to mental health crises before Public Safety is called. She said when she did have to call Public Safety, she was not pleased with how the officers handled the students in distress.

“They ask a few questions, a lot of them are really straightforward like ‘Were you trying to kill yourself?’ just like that,” Cady said. “I have my opinion, which is that that question should not be asked in that way, especially by [Public Safety officers] where usually, they’re almost screaming these questions.”

She said she feels like Public Safety officers know how to assess mental health crisis situations well. However, she said there needs to be someone with more training handling the social aspect of talking to students experiencing mental health crises rather than the officers.

In 2016, an external report on Public Safety found that many students believed the Office of Public Safety was not adequately equipped to respond to mental health crisis calls. The report also made over 40 recommendations for how Public Safety could improve and create a better reputation.

Brian Petersen, director of the Center for Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS), said there is currently a group of administrators that is looking at different colleges across the country to see how they are handling crisis counseling. However, he said the group is early in the process.

“IC is listening to students, getting student comments and student experience, especially in the residence halls, that is driving this search for different ways to respond to students in distress,” he said.

Dean of Students Bonnie Prunty said the campus is currently in the process of becoming a JED campus as part of the JED Foundation. JED is a nonprofit organization that works to prevent suicide and protect mental health of teens and young adults. Prunty said the college is working with JED to look at what areas of the college’s mental health services could be improved.

“One of the areas we are looking at is what opportunities might exist to improve the support available for these students outside of regular business hours, including who initially responds to requests to check on a student’s welfare,” she said via email.

Petersen said conversations about how Public Safety handled psychological calls started because of how students were transported to Cayuga Medical Center. He said that as of Spring 2020, students are no longer transported by Public Safety, but are instead transported in an ambulance. He said part of the reason was because of safety concerns surrounding COVID-19.

Petersen said students were also sometimes placed in handcuffs when being transported by Public Safety.

“Now we’re looking at the issue of what does it mean if a uniformed officer arrives to respond to a student in distress, versus residence–life staff, versus counseling staff,” he said. “We are trying to look at all of those scenarios and see how we can create the least stigmatizing and most responsive way of responding.”

Freshman Skye Moricz said they made an appointment at CAPS early in Fall 2021 because they were not feeling well mentally.

“They sent me to the Cayuga Medical Center, but I didn’t know I was going to be there for more than a week,” they said.

Moricz said there were two Public Safety officers waiting outside of CAPS when they left to be transported, which made them feel uneasy. Moricz said they were transported to the hospital via ambulance instead of being transported by the Office of Public Safety. Moricz also said that despite saying they were feeling mentally better, they were still deemed “unsafe” by mental health professionals.

“CAPS and Public Safety, even though they were being very nice and very understanding about everything, they couldn’t do anything,” they said.

Moricz said they felt unsafe at Cayuga Medical Center because they are part of the gender identity. They said it was overall a very difficult week, and it made their mental state worse. They said unfortunately they missed a week of classes because they were not allowed to have any electronics because of being in the behavioral services unit.

“They said it was the best for me, but it didn’t feel like it was the best for me,” they said.

Tom Dunn, associate director and deputy chief of Patrol and Security Services, said officers determine if a student needs to be transported to the hospital by adhering to the New York state mental hygiene law and determine if the student is acting in a manner that could potentially pose serious risk to themselves or others.

“Likelihood to result in serious harm shall mean (1) substantial risk of physical harm to himself as manifested by threats of or attempts at suicide or serious bodily harm or other conduct demonstrating that he is dangerous to himself, or (2) a substantial risk of physical harm to another persons as manifested by homicidal or other violent behavior by which others are placed in reasonable fear of serious physical harm,” the law states.

Between July 1 and Sept. 20, Public Safety has responded to a total of 12 mental hygiene calls, meaning students experiencing a potential mental health crisis, and 11 welfare checks, where students want to check on peers who they are concerned about. Of the 12 mental hygiene calls, 11 resulted in a student being transported to the hospital under section 9.41 of the New York state mental hygiene law, meaning an officer determined the student needed to be transported because the student was determined to be a threat to themselves or others. One student was transported under section 9.45, meaning that a counselor decided the student needed to be transported.

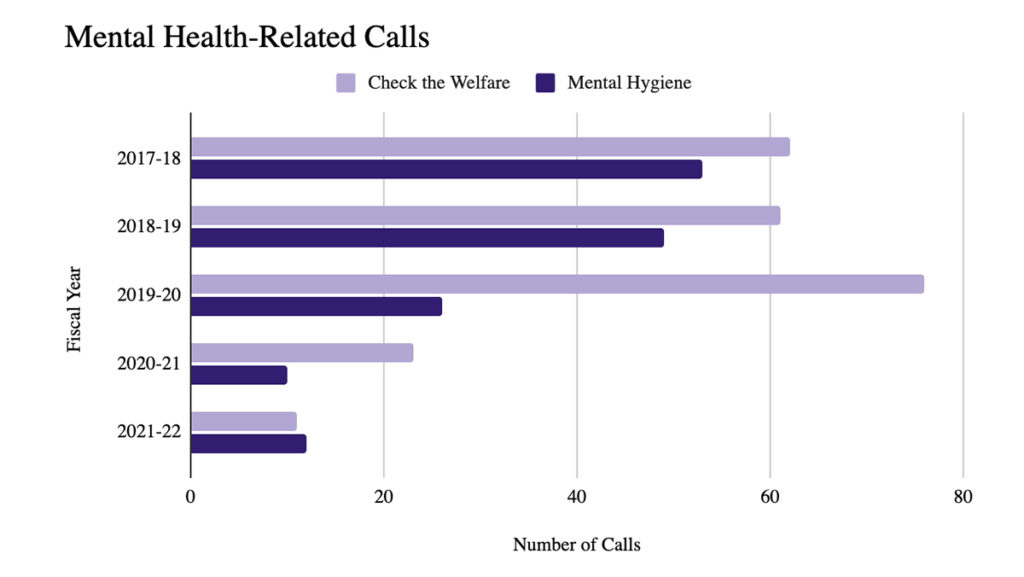

Since 2017, the college has seen a decrease in the number of psychological related calls and the number of students transported to Cayuga Medical Center. In the 2017–18 academic year, there were 53 mental hygiene calls and 62 welfare checks; in the 2018–19 academic year, there were 49 mental hygiene calls and 61 welfare checks; in the 2019–20 academic year, there were 26 mental hygiene calls and 76 welfare checks and in the 2020–21 academic year, there were 10 mental hygiene calls and 23 welfare checks. However, during the 2019–20 and 2020–21 academic years, there were fewer students on campus because of the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning the numbers may not represent how a full year would have gone.

The Associated Press (AP) found that the number of college students receiving mental health treatment has risen to 35% since 2014. Despite a decrease in mental health stigma, the percentage of college students who have contemplated suicide has increased since 2010, according to Statista. Petersen said there have been 350 students who have scheduled appointments with CAPS this semester. He said this number is higher than usual for this time of year. He said over the past three years CAPS has seen 17–20% of the student body each year.

Petersen said CAPS works with and provides some training to Public Safety officers regarding mental health–related calls.

Dunn said Public Safety officers attend a six-month training course to become officers, and part of their training is about how to respond to mental health-related calls. He said officers also receive more mental health training during their on-the-job training.

Bill Kerry, executive director of Public Safety and Emergency Management, said via email that the overall goal is to reduce the number of times a Public Safety officer is the first responder to a mental health call.

“I think the public safety officers currently do a great job overall of assessing these situations and resourcing students, however, in some instances, having an officer arrive may add to the existing crisis, so we are trying to work on eliminating that to the best of our ability,” he said via email.

Dunn said if any student is unsatisfied with how an officer handled a call, it can be reported by calling Public Safety.

In 2020, 36.9% of college students said they were receiving mental health services and had also seriously considered suicide, according to Statista. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that in 2017, 10.6 million Americans had considered suicide and 1.4 million people attempted suicide.

Suicide Prevention Week was Sept. 5–11 and September is Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, but Petersen said the college was unable to plan any events for this year because of CAPS experiencing an increase in appointments. However, he said having discussions about suicide is incredibly important.

“I think it’s important for people to be able to talk openly and honestly about suicidal thoughts and feelings because the truth is that many people are having them and not verbalizing them,” he said. “That doesn’t mean that they’re going to act on them, but they’re walking around suffering.”

Petersen said many people might not know where to go to discuss suicidal thoughts, feelings and mental health in general, or people may be apprehensive about counseling. He also said people may not want to have conversations about suicide because of the myth that someone who talks about suicide will act on their suicidal thoughts.

“We as a society need to become much more comfortable with asking people how they’re feeling and if they’re feeling suicidal, being able to meaningfully have a conversation about that and destigmatize it,” he said.

Students can call CAPS at (607) 274-3177 at any time to schedule an appointment or speak to the after-hours counselor or Public Safety at (607) 274-3333. Students can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number at (800) 273-8255 or the Trevor Project at (212) 695-8650.