Update Jan. 31: The patient who alleged she and Shirley M. Collado — who was her therapist in 2000 and is now the president of Ithaca College — entered into a sexual relationship in 2000 has come forward to affirm that she stands by the account of the case she gave the prosecution in 2001. The patient also said she did not send the anonymous packages that were circulating with information about the case and does not know who did.

Original: Ithaca College President Shirley M. Collado was accused of sexually abusing a female patient while working as a psychologist in Washington, D.C., in 2000 and was convicted of sexual abuse in 2001.

Prosecutors argued Collado took advantage of a vulnerable, sexual-abuse survivor with mental illness by entering into a monthslong sexual relationship that started when Collado was the patient’s therapist. Collado denies having any sexual contact with the patient.

Collado admits to living with the patient after the latter was discharged from The Center at the Psychiatric Institute of Washington. This violated her employment contract at The Center — a program specializing in post-traumatic and dissociative conditions at a private psychiatric hospital — as it was considered to be an unethical outside relationship and grounds for immediate termination. Collado said she was trying to help her by providing her a place to stay.

Collado pleaded nolo contendere — no contest — to one count of misdemeanor sexual abuse in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia in August 2001 for a sole charge of placing her hand on the patient’s clothed breast with sexual intent while Collado was her therapist. Collado knew, or had reason to know, that the sexual contact was against the patient’s permission, as the patient was an inpatient at a psychiatric hospital, according to the charge against Collado.

“The laws and ethical rules prohibiting sexual and outside relationships with former or current patients are designed to prevent the very activity that occurred in this case,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Sharon Marcus-Kurn, the case’s prosecutor, wrote in the Government’s Memorandum in Aid of Sentencing. “The law recognizes that individuals that are wards of psychiatric institutions are extremely vulnerable to being abused and taken advantage of. The laws are designed to protect them and punish anyone who violates the therapist/patient relationship.”

By pleading nolo contendere, Collado did not admit guilt but accepted a conviction. After a defendant enters a nolo contendere plea, the case moves forward as though the defendant pleaded guilty. With this plea, there is no trial.

Collado maintains her innocence and said she never had any sexual contact with the patient.

“I didn’t have the legal resources; I didn’t have the financial resources to, and I didn’t have the emotional wherewithal to really take this on the way I would have preferred,” Collado told The Ithacan. “So I took a different route. And like many people in this country, young people in this country, people of color, people who don’t have networks, that was me. This happens all the time, where you make this really difficult choice, even if it goes completely against the truth of who you are.”

Collado was one of the the patient’s treating therapists when the patient was an inpatient ward between May 12, 2000 and June 9, at The Center, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

Collado, who graduated from Duke University with a Ph.D. in 1999, was 28 years old when she was treating the patient. She did not have a therapist’s license and was practicing under the supervision of a licensed therapist who was also employed at The Center, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

Marcus-Kurn wrote that the patient’s two therapists and The Center’s director — it is unclear whether Marcus-Kurn is referring to Joan Turkus, The Center’s medical director, or Christine Courtois, The Center’s clinical director — all believed the patient’s allegations. Marcus-Kurn wrote that the two therapists had known the patient for a long period of time through numerous hospitalizations.

“They both find her to be an extremely truthful person, and although she may have flashbacks of prior abuse or may relive traumatic experiences, her therapists have stated that she does not fabricate or hallucinate things that simply did not happen,” Marcus-Kurn wrote. “In other words, she has not experienced psychotic episodes and has never been diagnosed as psychotic.”

One of Collado’s co-workers at The Center, who was familiar with the situation and wished to remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of the story, told The Ithacan they believe the patient’s allegation that she and Collado had a sexual relationship.

“She had no reason to lie about them,” the co-worker said. “She had no reason to lie.”

The revelation of these accusations against Collado comes amid a national reckoning with sexual assault and harassment, reflected in the #MeToo movement, in which survivors of sexual assault and harassment are sharing their stories. The #MeToo movement has touched every aspect of society, including higher education.

Collado was sentenced to a 30-day suspended sentence, 18 months of supervised probation, an order to stay away from the patient, and 80 hours of community service. The court recommended that the community service should “not directly involve vulnerable people.” She was also ordered to pay $250 under the Victims of Violent Crime Compensation Act of 1981.

Chronology

The patient was receiving therapy for post-traumatic stress at The Center, as she had previously been sexually abused by a doctor — who was convicted for the abuse — and as a child, according to the prosecution. The patient, who was 30 years old at the time of the court case, was diagnosed with having bipolar disorder and a dissociative identity disorder and had experienced lengthy periods of deep depression and suicidal thoughts, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

The patient alleged that she began a sexual relationship with Collado on May 20, 2000, which lasted until October 2000, according to the prosecution. Marcus-Kurn wrote that the patient recorded encounters with Collado in a journal that was submitted to the court but is not included in the case file.

Marcus-Kurn wrote that the patient said the two first kissed after a therapy session on May 20. The patient said that some time between May 20 and June 9, 2000, Collado fondled her buttocks and directed her hand to Collado’s breast. She further alleged that after most individual therapy sessions, she and Collado kissed, usually going to private areas at The Center to avoid detection.

On two occasions, Collado fondled the patient’s buttocks and rubbed her inner thigh and pelvic region, the patient said.

Collado told her that their sexual contact would be “therapeutic” and would “bring her out of her shell,” the patient said. Collado denies this allegation.

Collado said she was working in the trauma unit at The Center when her first husband committed suicide on July 9, 2000, starting a very difficult time in her life.

She resigned from The Center as she was grieving her husband’s death.

“I, at that point, was sought out by a patient who I had treated before on the unit who really needed my help and was in crisis and didn’t have a place to stay,” she said.

The patient moved into Collado’s house “shortly after” her discharge from The Center, according to the prosecution. Collado supported the patient with a place to live after she was discharged from the hospital, Collado’s attorney, William Hickey, wrote in the defendant’s memorandum in aid of sentencing.

Marcus-Kurn declined to comment, and Hickey did not respond to a request for comment.

During this period of time, the patient and Collado lived with a third roommate, Alyssa Rotschaefer. Rotschaefer — who has since married and is now Alyssa Mueller — declined to comment.

The patient alleged that she had participated in a three-way sexual encounter with Collado and an adult male on Sept. 9, 2000, according to the prosecution. The patient alleged Collado told her it “would be psychologically helpful for her.” The man and Collado denied that the interaction had taken place.

Collado said the patient moved in either in the late summer or fall of 2000 and moved out by November after Collado asked her to move out.

“I learned, and it came to me, that that was probably not a good idea, that I needed to really focus on myself and that I was not in the position to help someone who I knew had a pretty troubled past,” she said.

The patient notified Nora Rowny, The Center’s social services director, about her relationship with Collado in early November, according to an email message Rowny sent to Turkus. The email was obtained and verified by The Ithacan. Turkus forwarded the message to Courtois.

Rowny wrote in the email that on Oct. 30, 2000, the patient called her and told her she had “lost her housing, felt betrayed and frightened and wasn’t sure where to go” and that she needed to move out in two weeks. Rowny wrote that the patient told her on Nov. 4, 2000, that the patient had a relationship with Collado, saying she had been living with Collado and they had been having a “‘sort of’ relationship” that began when she was a patient at The Center. She told Rowny she and Collado had “expressed a mutual attraction and that Dr. Collado had kissed her” two weeks before her last discharge from The Center. The patient told Rowny she continued to call and see Collado after leaving the unit.

The patient told Rowny that Collado had asked her to move in following the suicide of Collado’s husband, and that she gave most of her furniture to Collado’s brother and moved in. The patient told Rowny she and Collado “became more sexually intimate and that she often slept with Dr. Collado” after she moved in.

But the patient told Rowny that tensions had risen between her and Collado over Collado’s involvement with a man; that the patient doing chores around the house triggered Collado by reminding her of her late husband; and that Collado was upset after she learned the patient told one of her other therapists, Amelie Zurn, about their relationship. The patient said Collado asked her to move out on Oct. 30, the day the patient called Rowny asking for help.

Rowny wrote in the email that she called Zurn on Nov. 4, 2000. Zurn said the patient “had told her about the involvement with Dr. Collado only recently.” Zurn told Rowny she was not sure what to do as “the story unfolded slowly concerning the extent and timing of the relationship.” By the time the patient told her about it, Zurn said, the patient had not been at The Center for a few months and Collado was on leave.

Rowny wrote that Zurn said she had decided not to immediately disclose the relationship since the patient said she was invested in her relationship with Collado and had told Zurn not to get Collado in any trouble. Zurn said alerting others would be a breach in her therapeutic relationship with the patient and that the patient may “decompensate lethally” if Zurn alerted leadership at The Center too quickly. The patient had told Zurn she had ruled out returning to The Center in case of decompensation because of her relationship with Collado and would not “easily accept hospitalization elsewhere.” Zurn said she was afraid the decompensation without the patient’s regular hospital could be lethal.

Zurn and Rowny discussed the matter and decided it would be best for The Center to be aware of the situation, as the patient had told both of them about the situation.

Courtois, Turkus, Zurn and Rowny all declined to comment. The patient also did not want to discuss the case.

Collado’s employment agreement with The Center stated that “any personal/friendship, intimate/sexual, or business (apart from clinical referral and services) relationships with a current or former patients constitutes a dual relationship and is an ethic violation. Any such relationship is grounds for immediate termination of employment,” according to the prosecution.

Collado said the patient needed her help.

“One of the things that is really hard when you are doing work, especially around trauma, is I think all good therapists see people as whole people, and I thought that I was making a thoughtful decision, and then I quickly learned that I wasn’t,” she said. “I put myself at risk by allowing her to live in my home.”

She added that she was on leave, not working at the clinic, when the patient moved in.

“I treated this person with integrity as a psychologist, I treated her on the unit appropriately and professionally,” she said. “And then I took a leave and again, I tried to help and make a decision, and then these allegations were made.”

Collado was suspended from The Center following the revelation, Marcus-Kurn wrote. Collado said she was on leave from The Center after her husband’s suicide and decided to resign after she realized she needed to spend more time grieving her husband’s death and was not in a position to return to the intense therapeutic work at The Center. Hickey wrote that she resigned and was not terminated.

The Psychiatric Institute of Washington was acquired by new owners in 2014 and has no records or information on the situation, a representative said.

The co-worker said that The Center had approximately 15 to 20 patients and 10 staff members, who were caught off-guard by the allegations.

“People were very shocked and very betrayed, because it struck at the heart of what we were trying to do with the patients who suffered trauma,” the co-worker said. “They need to have very strict boundaries and relearn what normal separation is between people. We tried to build up those boundaries — internal boundaries and external boundaries — so they can get through the world.”

Legal Case

In her interview with The Ithacan, Collado said that shortly after she asked the former patient to move out, she became aware of the claims the patient made against her. She said she did not have the resources to fight the allegations and wanted to take care of herself and figure out a way forward.

Collado pleaded nolo contendere on Aug. 29, 2001. By entering this plea, Collado waived her right to a trial by jury or the court and gave up her right to appeal the conviction in the Court of Appeals. The three conditions of the plea were that the government would allow the no contest plea, the government would recommend suspension of all jail time if the judge considered incarceration, and the government would not pursue any other charges based on the allegations to date.

Marcus-Kurn wrote Collado had met the patient when the patient was emotionally vulnerable, had encouraged the patient to open up to her and knew the patient had been sexually abused in the past. After Collado realized she did not want to continue the relationship, she ended it abruptly, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

“The defendant had to have known that, in the long run, her relationship with the victim would cause great emotional damage to the victim,” Marcus-Kurn wrote.

The patient told Marcus-Kurn that she was emotionally unable to write a formal letter to the court. While she said she really wanted the court to know how she felt, she was concerned reliving the painful experiences could lead to suicidal thoughts she was unsure she had the strength to fight.

The patient did express her feelings to Marcus-Kurn over the telephone. Marcus-Kurn wrote that the patient said the following:

“It brings on such immense pain and it is very, very intense feelings of confusion. I start hearing her calling her name, I start smelling her, I start remembering her telling me that it would be good for me to sleep with (name redacted) , and I remember being raped, and I have blocked that all out and I’m afraid that it would kill me if I start dealing with it right now. She has hurt me beyond belief and it’s like so bad that I can hardly touch it because it hurts so bad. I have to take it really slow. I know that I feel a lot inside but I’m not really sure what all of those feelings are because I try really hard not to feel them but I know that they are painful as hell. I literally feel that I will fall apart every time I think I’ll deal with it. And it hurts too much. And I’m really angry that she slept with me and that she convinced me to sleep with her boyfriend and I feel that I was raped and that there is nothing I can do with it because I believe it isn’t against the law in D.C.”

Collado’s lawyer made a motion to strike the victim impact statement from the case, arguing that victim impact statements were intended to be used for crimes of violence, not misdemeanor assault charges, and that the prosecution did not follow the correct procedures to attain it. The judge struck the patient’s statement from consideration.

The patient sent Courtois and Turkus emails she alleged were from Collado and photographs from a trip to New York she had taken with Collado, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

Collado would not discuss the alleged trip to New York with The Ithacan and said she did not want to go through every claim the patient made, as she had already gone through a court case.

“Just to generally say, when she lived in my home and when I was trying to help, I tried to be a normal roommate and a kind person and be able to be helpful like I did with my other roommate living in the home and, you know, my friends and family,” she said.

Marcus-Kurn included the emails that the patient claimed were from Collado in the government’s memorandum in aid of sentencing. One sent on Oct. 10, near the end of their relationship, stated:

“I have grown to be very attached to you and don’t want anything to hurt you in any way. The thought of losing you is overwhelming…When I told you that it scared me and that it made me less capable of being close/intimate with you…I realized that you need CLEAR boundaries with me. I realized that I just want to be your friend…I have tremendous love for you. I care about you deeply…I realize that this is a huge loss for you, but I don’t think that we can afford to do anything more. It has become too confusing and too sticky when the boundaries are loose… [Regarding (name redacted)], [h]e wants to be your friend. He has no regrets about being intimate with us or you being intimate with me, but he does not agree with any unclear stuff (i.e. you wanting to still be with me, etc.)… Please don’t hurt (name redacted) with details about “us” or how you feel about me. Just keep the promise of loving me unconditionally. I want to offer that to you. You have not lost me. You have lost an aspect of our relationship. I don’t regret it. It gave me tremendous gifts and insights…I am also going to stress that I am keeping this between us.”

The other email the patient alleged Collado sent her read:

“As for us, I must tell you that not a day goes by that I don’t regret mixing everything up, setting poor boundaries and misleading you/(name redacted)/etc. in any way…Anyway, all this is say that I am not good for you, [patient]…As far as (name redacted) is concerned, we are working on many things including what we gained and lost from being intimate with you, building trust between us, deciding what we can be open about at this point…”

Collado denies writing the emails.

“I don’t know where these came from,” she said. “I didn’t write any of the emails. And, in fact, if you’re looking at the court documents, you will see that my lawyer made it very clear in my statements that had I gone to trial, I had credible people, and I think it’s written in there very carefully, about the allegations about the emails, details of emails that were not mine.”

Hickey wrote in the defendant’s Memorandum in Aid of Sentencing that Rotschaefer — Collado’s other roommate — would have testified that the patient had access to Collado’s computer and it became a “problem,” as the patient was frequently using the computer. Hickey wrote that the defense also would have called an expert witness, forensic expert Gerald R. McMenamin, who would have testified Collado was not the author of the emails and that the patient was most likely the author.

McMenamin told The Ithacan that he did not recall working on or forming an opinion on this matter, and said he that even if he did recall it, he would not be able to comment on it, as it was not presented as testimony in court.

“Additionally, what someone ‘would have testified to’ is not evidence and should not be used as a basis for argument,” he said.

Marcus-Kurn wrote that when Collado was confronted by “The Center Director,” she admitted she had been living with the patient and that she and the patient had been in the area of The Center where the patient alleged some of the sexual contact had occurred. But she denied any sexual relationship, Marcus-Kurn wrote.

Collado denies speaking with either of the two directors of The Center.

“When I learned about the allegations, I attempted to contact them and talk to them, and I never had a conversation with them,” she said. “They never talked to me.”

At the time, Collado was also working part-time as a youth and family psychotherapist at the Multicultural Clinical Center in Springfield, Virginia. Collado said the Multicultural Clinical Center was doing contract work for the County Attorney’s Office of Arlington County.

Marcus-Kurn wrote that “The Center Director” contacted that office after the revelation of the allegations and that Collado was approached by “the supervisors of Child and Family Mental Health Services at the Arlington County Office.” In that discussion, Marcus-Kurn wrote, Collado denied any personal relationship and said she had only allowed the client to store personal belongings in her garage, but that the client had gotten upset when Collado asked her to remove the belongings.

“I don’t know if that happened; that’s what they wrote,” Collado said. “It’s so long ago. I talked to one of my colleagues there at some point. I wasn’t there full-time. Again, I mean, I guess I just go back to, I have said from the beginning, and so it’s very consistent, that … I have denied these allegations the entire time. There was not one moment where I said the opposite of that. So just… that’s all I can say.”

Rebecca Keegan, director and founder of the Multicultural Clinical Center, did not respond to a request for comment. Jessica Perkins, a legal assistant at the Arlington County Office of the County Attorney, said Collado was not employed at that office at any time in any capacity.

The defense maintained that Collado had encouraged the patient to work with her multiple personalities by doing artwork and keeping a journal.

“Dr. Collado attributes [the patient’s] belief of ongoing sexual encounters as fantasies and aberrations,” Hickey wrote in the memorandum. “At no time ever did Ms. Collado tell [the patient] that acting out sexual fantasies with others would be therapeutic.”

The prosecution submitted a letter from Courtois and Turkus to Judge Frederick Dorsey as a supplemental submission in aid of sentencing. Though the document introducing this letter to the case is included in the case file, the letter itself is not. The letter was obtained and verified by The Ithacan.

Entering into a sexual relationship with a patient is against the American Psychological Association’s Code of Ethics, Courtois and Turkus wrote.

“Her conduct, in terms of entering into a personal relationship with a patient, is not only a violation of the ethical code of her chosen profession and her contract with her employer, but a betrayal of those who trained her and of all of us in the field,” Courtois and Turkus said. “She neither sought supervision nor support from her colleagues when she violated the code; instead she kept it hidden.”

In the letter, Courtois and Turkus wrote they encouraged “due consideration of restricting Shirley Collado from employment involving patient contact” and wrote they had “grave concerns in this area.”

“It has been a shock to us to discover this months later and has shaken us to our professional core,” Courtois and Turkus wrote. “The damage to the hospital program, in which she worked, is inestimable. Many hours have been spent by us and our staff in processing these issues. We will undoubtedly continue to do so for some time to come. What Shirley Collado did is the antithesis of all of our beliefs, values, and responsibility to patients.”

In their letter to the judge, Courtois and Turkus wrote they also made a report to the Board of Psychology of the District of Columbia. A Freedom of Information Act request filed by The Ithacan revealed the board has no records regarding Collado. Ed Rich, senior assistant general counsel for the District of Columbia Department of Health, said the board has no jurisdiction over a health professional prior to their licensure and would not speculate as to what the board would have done with a report of wrongdoing by an unlicensed individual.

In the defendant’s Memorandum in Aid of Sentencing, Hickey wrote the patient’s allegations were “reckless and spurious.”

Hickey wrote that the patient was diagnosed with a brain tumor and had hallucinatory episodes. On “several occasions,” the patient thought someone else was in the room with her and Collado and confused Collado with other people, Hickey wrote. He wrote that Collado’s accuser “suffers from psychoses and is highly unstable and unreliable” — although he cites no source for that diagnosis. The claim contradicts what those who treated the patient told the prosecution.

The patient was not psychotic, the co-worker said.

Collado said she fully stands by what her lawyer submitted in her defense and could not talk about the patient’s medical history.

“I can’t speculate why the therapists reported what they did,” she said. “What I can tell you, in a very general way, without disclosing her whole medical profile… this is someone who was treated multiple times — not just by me, by multiple hospitalizations and therapists — had a very serious psychiatric disorders that have lasted years upon years in a pretty serious profile when you look at dissociative disorders, psychotic disorders, things like that.”

Hickey argued that the patient did not register any complaints about Collado until after she was asked to move out in November 2000.

Hickey wrote that the fact the patient was unwilling to provide a written statement “should give serious pause to any credence attributed to her” and that “the fact that she never complained to anyone until she had to move out of the Collado residence should question her motivations.”

He also noted there had never been any other allegations made against Collado. Collado told The Ithacan there has never been another allegation of sexual misconduct against her.

Hickey wrote that the unit in which the patient was located was highly visible. He wrote that there were windows in therapy rooms, nurses noted where each patient was at all times and there were no places off-limits in The Center.

“Therapists have offices, and offices have doors,” the co-worker told The Ithacan. “And people do therapy behind closed doors.”

Rotschaefer told Hickey that the patient “was extremely unstable, unreliable and had a crazy lifestyle.” Rotschaefer said she never knew or observed an inappropriate relationship between Collado and the patient.

Collado was sentenced on Nov. 20, 2001. The prosecution requested she be sentenced to go to counseling for mental health providers who sexually assault their patients, perform 120 hours of community service, and write the victim a letter of apology. Dorsey sentenced her to a 30-day suspended sentence, 18 months of supervised probation, an order to stay away from the patient, and 80 hours of community service.

Leah Gurowitz, a spokesperson for the District of Columbia Superior Court, said no transcript explaining the judge’s sentencing decision is available and that Dorsey has retired. Dorsey said he did not recall the case when reached by The Ithacan and that it is not his custom to discuss specific cases. He said a case in which a nolo contendere plea is entered proceeds the same as an admission of guilt for the purposes of the law.

“Then I proceed on sentencing based on the circumstances and background of what is alleged in the case and the information that is provided by the lawyers,” Dorsey said.

The probation was transferred to New York, as Collado had moved to New York City by the time she was sentenced.

Ethical Issues

Eric Harris, a licensed psychologist and attorney who is currently the legal counsel for the Massachusetts Psychological Association, had approximately 60,000 consultations with psychologists while he worked for the American Psychological Association Insurance Trust, which changed its name to the American Insurance Trust. Though unfamiliar with the specifics of this case, he spoke with The Ithacan about the wider ethical issues involved.

Harris said living with a former patient is an ethical violation due to the power differential between the therapist and patient. He said that when a client comes to a therapist and requests help, the therapist should be completely devoted to the interest of the client. But that changes when therapists enter any type of personal relationship — such as living together — with a former patient.

“When a client develops any type of personal relationship with their therapist, when they are no longer in therapy, the client begins to expect that the therapist will continue to behave like a therapist,” he said. “But often, when you have a personal relationship with somebody, you don’t behave like you’re a therapist. You behave like you are a normal human being, and that means you have needs of your own. That can lead to disagreements and fights.”

Harris said patients are very vulnerable when they enter therapy. If anything goes wrong after a therapist enters into any type of personal relationship with a patient, it is much more harmful, he said.

Collado said she couldn’t anticipate how the patient would feel after being asked to move out.

“I’m sure she was confused and felt rejected or hurt, and clearly — within a matter of a week, days — she’s … making claims about something she alleges that I did when she was being treated, and that simply did not take place,” Collado said. “I’m sure she felt a lot of things.”

Susan Roth, professor emeritus of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, met Collado when Collado was a graduate student and has remained in touch with her. Roth is an expert in trauma therapy and said she does not believe the allegations of sexual misconduct against Collado.

Roth said that generally speaking, she would recommend against a therapist living with a former patient. But she said that considering the context of the situation, Collado feared for the patient’s safety, did not feel at risk for having an inappropriate relationship and had other people living in the house, she doesn’t hold it against Collado.

“I think the context in which it happened — and she was in training on top of that — the harm was done to her and not to the patient,” Roth said. “If I weren’t confident that she had boundaries, if I thought that would put them at risk for having a relationship, yes, then I think, even with a former patient, having some kind of romantic or sexual relationship of any kind, I would not feel good about. But that is not what happened. It’s an easy call if someone knows Shirley. Without knowing Shirley, it’s not such an easy call… If you asked me, do you think it is okay for anybody to do that, I would say no, not in general.”

The co-worker said that The Center had very strict rules and that employees were not allowed to hug or touch the patients or give them rides to the bus station, for example.

“The sexual stuff aside, there were so many boundaries broken there,” the co-worker said. “We needed to model perfect boundaries at all times. For someone who is supposed to be a trained expert to come in and do something like this that broke every rule, and every therapeutic rule of making boundaries, that was not good.”

They said these rules were made very clear and explained to all the employees.

“It is difficult, and people make mistakes,” the co-worker said. “People overstep the bounds, and that’s why we have supervisors upon supervisors. For example, to invite a patient to come and live with you, that would be something you’d have to talk to your supervisor about, and I can guarantee you, they would say hell no.”

Harris said entering into a sexual relationship with a patient is “about one of the most harmful things you can do as a therapist.”

“If you have sex with an existing patient, in psychology there is only one mortal sin, and that’s it,” he said. “The whole issue of sexual harassment, and #MeToo now … involves the question of consent. And in the opinion of the profession, there is no way a current client, given the power differential in the relationship, can meaningfully consent to a sexual relationship. The reason it is such as serious violation is we know the amount of serious harm that clients have suffered as a result of being abused in this way.”

The patient would have understood that engaging in a sexual relationship with a therapist would be a violation of The Center’s rules, the co-worker said. The patient was unable to consent to sexual contact because of her status as a trauma patient, the co-worker said.

“It would be like seducing a child, honestly — that’s how vulnerable… you just don’t do that,” the co-worker said. “I would not say that she would be capable of giving consent.”

Presidential Search

Despite the conviction, Collado rose through the ranks of higher education. She left D.C. and moved back to New York, taking a job at the Posse Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes college access and youth leadership development. Collado had attended Vanderbilt University as a member of the first group of Posse Scholars and graduated in 1994.

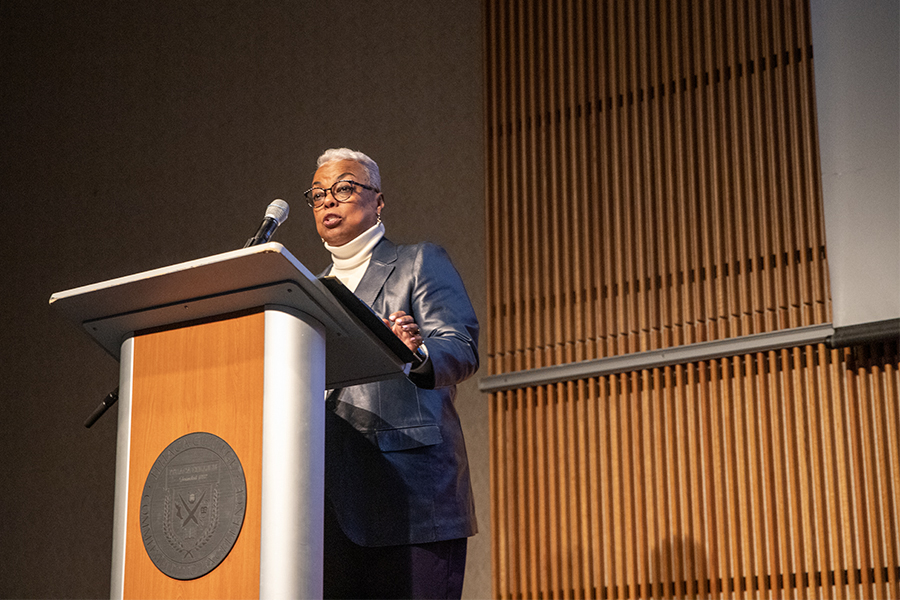

After leaving the Posse Foundation in 2006, she held administrative roles at Middlebury College, Lafayette College, Rutgers University–Newark and, now, as president of Ithaca College. Collado began her tenure as president on July 1, 2017. She also serves on the Board of Trust at Vanderbilt University.

Tom Grape, chair of the Ithaca College Board of Trustees, and Jim Nolan, trustee and chair of the search committee, said the case was thoroughly vetted during the search process.

“We had very thorough and comprehensive discussions with Shirley about this issue with the search committee and, ultimately, with the board,” Grape said. “So it was very open discussions, and we talked with some of her previous employers and references about this matter, so it was something that was very openly discussed, that we knew all about.”

Grape and Nolan would not reveal which references the board or search committee spoke with, or if the board or search committee spoke with anyone who oversaw Collado’s work at The Center, saying they had promised confidentiality with the references they spoke with.

“My own perspective about it is this is something of almost 20 years ago that was adjudicated in court and has been settled,” Grape said. “And I think for us to sort of go back and ask people, well, something that happened 20 years ago when there’s since been a 20-year history of behavior that is spotless, to me, the matter was settled with the court action 20 years ago. And we’ve done very thorough reference-checking for her professional activity since, and we did talk to some folks from that era, and we’re satisfied.”

While the presidential search began as an open search, meaning final candidates would be publicly identified and would interact with the campus community, the search became closed in December due to feedback from the candidates and the search firm, Spencer Stuart. This follows the trend in higher education of having more confidential searches.

Nolan said he believes Collado’s denial “100 percent,” and Grape said he does not believe the allegations of sexual misconduct against Collado.

Grape said Collado has acknowledged that letting the patient move in with her was a mistake and that Collado was trying to be helpful.

“That’s the kind of person she is, and we think that’s her character, of trying to be helpful to folks,” he said. “And she acknowledges she, in retrospect, wouldn’t do that again. … Her ethics are of the highest order, and we are not concerned about ethical breaches in the past 20 years or going forward.”

While the board of trustees examined all the court documents, the search committee — which consisted of trustees, faculty, students and staff — reviewed only a summary of the court documents provided by the board. Nolan said he feels the search committee had the pertinent information. Both the board and the search committee discussed the matter with Collado in-depth, Grape said.

“The search committee was fully aware of the contents,” Grape said. “But they’re very sensitive documents, and we wanted to be careful about the distributions.”

The court documents are available to the public, upon request to the District of Columbia Superior Court.

Nolan and Grape would not share with The Ithacan what information the search committee received and how the court documents were summarized for the search committee.

“The search process, by its nature, is a very confidential process, and I think to recreate documents and start making those public would not be in anyone’s best interest,” Nolan said.

Grape said the board had all the documents and went through them in great detail.

“The board, who ultimately makes the hiring decision, did have all the documents and did have a chance — several chances — to meet with Dr. Collado and go through it in great detail,” he said. “The board was satisfied with information they read and with the conversation they had and the due diligence that we’d done.”

Nolan said Collado described the incident during the search process similarly to the way she did in a Q&A with IC View released by the college on March 1, 2017, shortly after the board of trustees announced her hiring Feb. 22, 2017. In the interview, Collado discussed the death of her first husband, the difficult period in her life and how a former patient made false claims against her after she asked the former patient to move out. She didn’t reveal that she was charged with and convicted of a crime or explain the specific nature of the charges against her in the IC View Q&A.

The Ithacan received an anonymous package in early December including the prosecution’s memorandum and some additional documents not included in the case file. Collado said her office also received an anonymous package with information from the case, which was reviewed by Grape and others.

“From the beginning, with the the board and the search committee, this is not news, this is not something that was unknown, this is not something that is a big surprise,” she said. “It’s something that the right people, at the right time, thoroughly investigated and looked at carefully, and I was completely transparent and forthcoming.”

She said she made the intentional decision to publicly talk about the case in the IC View interview.

“I cannot control what has been disseminated, how one-sided it might be,” she said. “I cannot control how people are interpreting the documents. … All I can do is give you my facts and my truth and try to share, as I have, with the board, with the search committee, and with the IC community my part of what actually happened.”

Grape and Nolan said they both absolutely stand by their decision to hire Collado.

“In any situation, you have to look at the entirety of the individual and the work that they have done,” Nolan said. “And there are challenges in people’s lives. So you take the whole body into consideration, and when we take the whole body of work, of her life experiences, into consideration, she is an exceptional individual … who we believe is absolutely the right fit for the institution.”

Editor’s Note: The patient’s name has been redacted, as The Ithacan does not identify victims of a crime. The headline on this story has been adjusted to better represent the story.