Some Ithaca College students and faculty members have mixed thoughts about the proposed scheduling grid for Fall 2023, which is designed so that the length of certain classes will reach 100 minutes and allow students to only have to take a course twice per week.

Provost Melanie Stein said via email that the scheduling grid is used to establish common college-wide time slots into which classes can be scheduled. Blocks of time are portioned out in order for students to take courses without time conflicts. Stein said that in previous semesters, classes were based on a three-credit foundation where 50% of four-credit courses had to be “off-grid” credits, meaning they did not match up with the specific times within the design of the schedule grid.

Off-grid courses are classes that do not match up with the scheduling grid of a college or university. They could cause conflict for students since they do not match up with the times when courses are scheduled within the grid. They may also overlap with other courses that are a part of the grid, known as “on-grid” courses.

The reasoning provided by the Offices of the Provost and Registrar in a Nov. 18, 2021, Intercom message explained that creating a modified scheduling grid had been a piece of the Ithaca Forever plan, the college’s five-year strategic plan created in 2019.

The first step of this action group before the pandemic was to examine data and find evidence of issues in the current scheduling grid. According to the Nov. 18 Intercom message, this information primarily came from survey responses from department chairs and students.

Stein wrote in an email that an early action group created by the college called Common Academic Experience was able to do some testing of proposed grids in 2019; however, the developments of the action group were disrupted because of the pandemic.

“The action group included administrators, faculty and students, and held focus groups with students, faculty and staff to review strengths and weaknesses of the schedule grid to inform decision making,” Stein said in an email.

In the Nov. 18 Intercom message, the Offices of the Provost and Registrar called for faculty and students to volunteer in order to have the opportunity to be a representative from one of the five schools. These volunteers would become members of the Curricular Revision Liaison Committee (CRLC) alongside staff from key campus offices, the deans of each of the five schools and Faculty Council.

The committee convened in February 2022 and had a goal of proposing a new grid by summer 2022. Michael Smith, adviser and professor in the Department of History, said that by the summer, the Provost and Registrar stopped responding to faculty emails regarding their concerns about grid designs.

While not on the committee, Smith said that by early September 2022, a new scheduling grid was designed, ultimately by the five deans and Stein; however, largely ignoring designs proposed by faculty. Once approved by the provost and the deans, the grid was shared with faculty in early October 2022.

“Many faculty members looked at this new schedule and said, ‘we don’t really see how we can do all the things that we’ve done with the schedule,’” Smith said. “It varies by discipline, like the science departments are really struggling to figure out how to do the labs the way that they always have. Humanities departments really wanted to set up seminar-like courses.”

Faculty members were asked to submit input about the proposed grid in a survey sent out in an Oct. 17 email, and are continuously encouraged by the Office of the Registrar to send feedback so the grid may undergo revisions as faculty draft their Fall 2023 schedules within the proposed grid. The college has asked faculty to make their schedules in accordance with the proposed grid in mind before providing feedback in the survey. However, no due date has been posted for faculty.

Ali Erkan, associate professor and chair in the Department of Computer Sciences, said there should have been more testing of the proposed grid. Erkan suggested that some of the testing could have examined how the proposed grid would affect each of the college’s five schools individually and then the college as a whole.

Erkan said that there are two long term effects that he could identify in the proposed grid. He said that one would be restricting students who may have more than one major or minor while the other would be passing up a teachable moment for the college to demonstrate how to work together cohesively as a single unit on an issue.

“Problems are always avoided in different institutions, yet an educational institution should always strive to make each problem a teachable moment,” Erkan said. “Missing that opportunity would be a huge loss.”

Thomas Pfaff, professor and chair in the Department of Mathematics, said that the new design would reduce classes students could take by about 25% and that the proposed grid should have been tested during a semester while also using the current grid as a backup. Although Pfaff does not have an approach to doing this, he said that it may be hard work for the college, but it is risky to not do any form of testing.

“There should be a year where we officially use the current grid but behind the scenes also use a proposed new grid and new courses (mostly courses that moved from 3 credits to 4 credits) to see if courses can be scheduled effectively,” Pfaff said via email. “We should then also select random students and see how their schedule fits into the new grid. This would be a lot of work.”

Some students and faculty have found the decreasing enrollment at the college has resulted in a reduced course offerings over the past few semesters, which has created registration challenges.

Stein said the college is changing the grid in order to accommodate more courses by adding more blocks of time for more 4-credit courses. Stein also said that the number of credits required to graduate are not changing and will stay at 120 and nothing about tuition relative to credits taken is changing either. However, many 3-credit courses will be modified to become 4-credits.

“Without a grid, if every professor just decided by themselves when their classes would start and end, classes would end up overlapping in a very chaotic way, which would create lots of conflicts for students as well as problems for optimal classroom use,” Stein said via email.

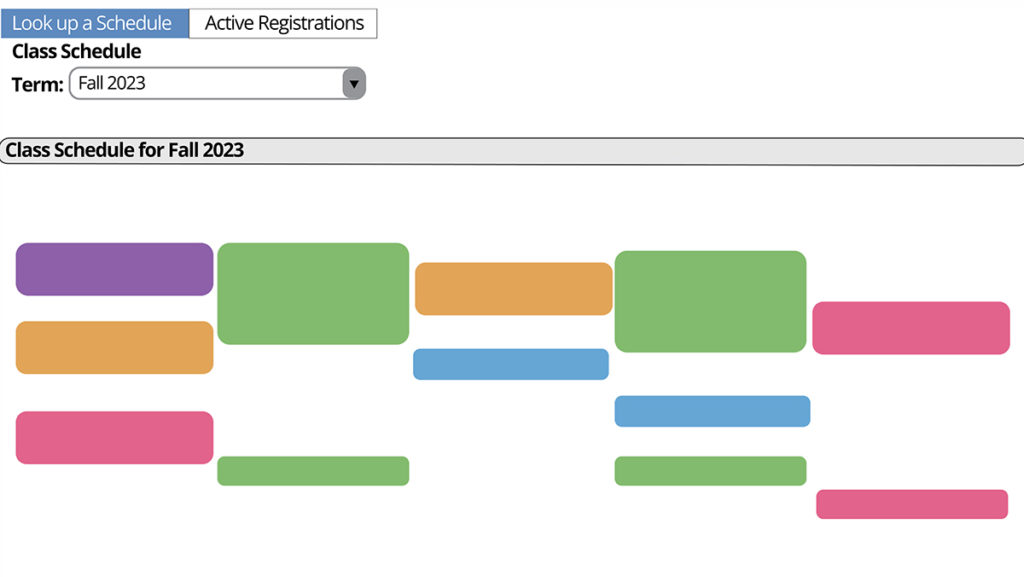

In comparison with the old grid, which has been used from 2006–2022, the classes are arranged so that there are not gaps in the time between classes. In the old grid, classes ran non-stop from 8 a.m. to 9:30 p.m according to the IC Service Portal. However, the new schedule grid has been designed with large chunks of time between classes, yet classes still run from around 8 a.m. until 9:35 p.m.

The scheduling grid used by Syracuse University ranges from 55–80 minute courses, which is more similar to the college’s proposed scheduling grid of offering from 50, 70, 75, to 100–minute courses. However, like the college’s current grid, Syracuse classes run consistently from 8 a.m. until 9:35 p.m.

Columbia University’s Master Course Schedule lists a range of courses from 75–150 minute courses, while the longest classes in the Ithaca College’s grid would only be for 100 minutes, while currently classes are typically 75 minutes long.

New York University has options for either 75 or 100–minute courses for each day of the week, which is similar to what the new scheduling grid would be offering in Fall 2023.

Pfaff said there are fewer time slots in the proposed grid, and there is more time in between classes than is necessary for the college to function.

“The new schedule has a ton of gray areas,” Pfaff said. “It makes for an inefficient schedule for students. It would probably make it harder for people to do other things if they had a campus job. I mean, for faculty, where do we schedule an office hour? A 20–minute office hour doesn’t help anybody.”

First-year student Delaney Jacobson said the proposition of extending classes to 100 minutes would be too long of a class time and said the current length of classes are long for her.

“I barely make it through the hour and 15–[minute] Tuesday and Thursday classes,” Jacobson said. “For me, it’s way too long.”

However, Smith said that the proposed grid could lessen the workload for students since it could lead to students taking fewer classes to complete the necessary amount of credits in a semester. Currently, students can opt either to take a 50–minute course on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, or take a 75–minute course on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Like Smith, Pfaff said this may help the workload of students but that it could also reduce time slots to about 40%. He said there could be more conflict for students and they could have less choices for their schedule.

Pfaff said that students in certain situations could be affected greater by the proposed grid than others, namely some first-year students.

“If you’re a music student, and you don’t take any courses outside the music school, well, you’re probably fine,” Pfaff said. “If you’re a senior PT major and you got your courses lined up in PT that’s fine. If you’re a second semester, first-year student [who is] not sure what you want to do, I can start seeing how it’s going to be really hard for them to get the kind of selection of courses they might want, but I don’t really know.”