Like many colleges and universities around the country, Ithaca College’s number of reported rapes has risen the past few years. But instead of calling for change, experts and administrators are praising the numbers as a sign that more crimes are being reported, not that the acts are increasing.

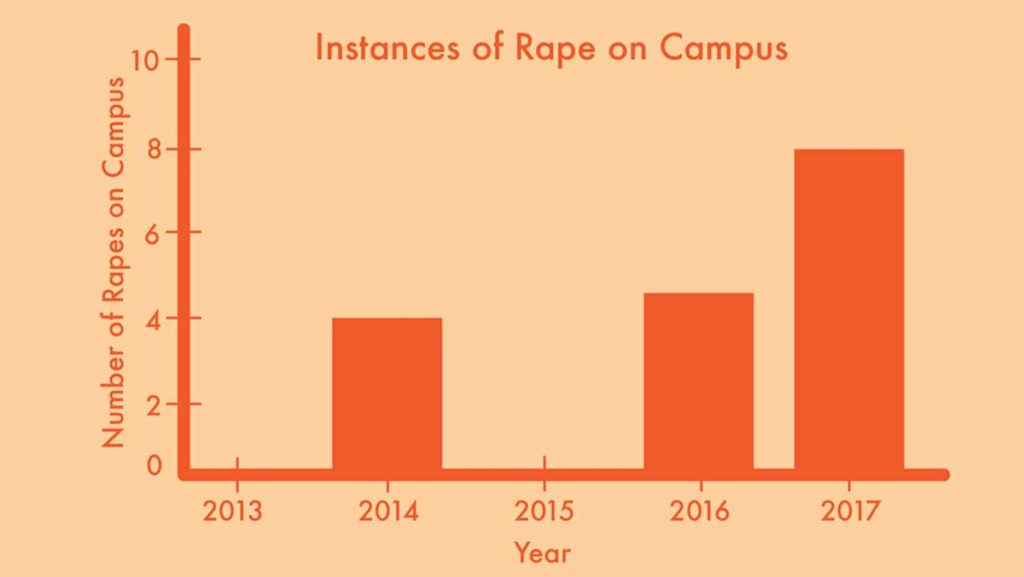

The Annual Security and Fire Safety Report at Ithaca College showed that eight rapes were reported in 2017. In 2016, there were five rapes reported, and in 2014, there were four. From 2015 to 2017, Cornell University recorded 2 rapes each year, according to the Cornell University Police Statistical Crime Record. From 2014 to 2017, the city reported two, 14, 10 and 10 rapes in each respective year, according to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services.

The National Center for Education confirms that the number of forcible sexual assaults has risen nationally as well, even though the total number of campus crime reports has decreased nationally. However, many experts and college officials have said that the increased reports do not reflect an increase in the number of sexual assault crimes being committed but an improvement in the systems and culture that allows people to increasingly report sex crimes. However, some are concerned that this logic does not allow the college to be held accountable for rising statistics.

“Although one sexual assault is too many, I don’t think the numbers are a poor reflection on our institution’s acknowledging it’s a problem,” said Tom Dunn, assistant director and deputy chief in the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management. He said he is not worried about the rising reports of rapes on campus and attributes the rise to increased reporting.

Title IX Coordinator Linda Koenig agreed with Dunn and said the rising report numbers may have been affected by the increased attention the issue of rape and sexual assault has been receiving on campus.

In the past year, the Title IX Office has expanded to include a deputy Title IX coordinator and has developed new programs for faculty and students. The office has collaborated with the Advocacy Center to run the “Bringing in the Bystander” program, which teaches students bystander intervention strategies, and created a new curriculum that faculty can use in their classrooms to teach students about affirmative consent.

“The more education and outreach we do to help people understand what their options are, what support they will get if they do report and more education about the system makes people feel more comfortable coming forward, and I think the numbers support that,” Koenig said.

Koenig said her office also collaborates with the Office of Public Safety and Emergency Management, the Advocacy Center and IC One Love to educate students about rape and dating violence.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey published in 2014, only 20 percent of rapes of college-age female students are reported, making it the most underreported crime in the U.S.

Dunn said that until the data in the annual report reflects the national averages, the rising rates could be considered an improvement. Koenig also said she thinks the increased reports are not a problem because it means the college is closing the gap between the number of rapes reported and the number of crimes committed. When reporting numbers become consistent, she said, those numbers will better represent the actual number of crimes that are committed.

“I think that data and other things would show that … when you make people aware of what their options are, reports go up, skyrocket,” Koenig said. “Then they might dip, a little and eventually, they kinda just level off. We haven’t seen that yet.”

However, Koenig said that there is no data to determine if the crimes are increasing or if the rising numbers are a result of increased reporting.

Senior Anna Gardner, president of Ithaca College Feminists United, said that although the campus climate at the college might contribute to the increase in reports, officials should not discount the problem that still exists.

“There’s this idea that because the culture is normalized to report these kinds of things or talk about it that that is the primary reason this is happening,” Gardner said. “I think that’s very possible, but there’s no easy way to say that’s why people are reporting. I think making sure that we don’t undermine the possibility that things are just continuing to get worse is important.”

Gardner said she thinks the officials on campus are still able to respond well to reports of sexual misconduct.

“I wouldn’t say that it feels like there’s any less accountability for that,” Gardner said. “The only thing that would be concerning is if someone said that rape isn’t a problem.”

Bonnie Fisher, professor at the University of Cincinnati in the School of Criminal Justice, has been the lead investigator on four federally funded projects to study the victimization of women and the prevalence of sexual assault on college campuses. She said she thinks it is plausible that the increased reports of rape and sexual assaults on college campuses are due to a changing climate surrounding sexual assault.

“I think there are several factors that may explain this, including schools’ reducing barrier to reporting, implementing campus climate surveys, activism on and off campus, including #MeToo,” Fisher said. “Society has changed worldwide with respect to sexual assault.”

Fisher also said data from the Clery Act — a federal law requiring colleges and universities that receive federal funding to disclose statistics about campus crime and security — only shows the number of reported incidents and not the full scope of crimes committed.

“The Clery Act is only one source — reported select types of crime. It needs to be supplemented with campus climate surveys so that the unreported incidents and barriers to reporting and help-seeking are taken into account by administrators,” said Fisher.

Robin Hattersley, editor in chief of Campus Safety Magazine, said in an email that colleges should attribute the increased statistics to increased reporting but that administrators should not lose sight that there is more work to be done to encourage more reporting.

“Unless your college’s sexual assault statistics are really high — like 10 percent of female students are reporting, not just experiencing, sexual violence — then your campus still has a long way to go,” Hattersley said in an email. “Your campus should continue working to encourage sexual assault victims to come forward as well as continue to say that an increase in reports is a good thing.”

However, Hattersley said that despite more widespread cultural awareness about sexual assault, there are many barriers to reporting.

“Even though the #MeToo movement is getting a lot of attention right now, we have to remember that this awareness is very, very new and there still are many significant barriers to sexual violence victims reporting their attacks,” Hattersley said in an email. “#MeToo is only a year old, and colleges really only became aware of the campus sexual assault problem a few years ago. We can’t expect this newfound awareness to completely erase the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years of human history when sexual assault was swept under the rug.”

One of the studies that Fisher led, “The Sexual Victimization of College Women,” found that sexual victimization on college campuses includes more than rape and that many women do not classify their experiences as rape for a variety of reasons.

According to the study, 2.8 percent of college women who responded to the survey experienced a completed or attempted rape in a six-month period, a result that means rates of rape victimization could reach almost 5 percent over the course of an entire academic year. This would amount to 97 women at the college over the course of a six-month period and near 174 women over the course of an entire academic year. The study found that statistically, it is possible that between one-fifth and one-quarter of college-aged women will experience completed or attempted rape victimization.

Fisher’s report also said rape goes unreported for many reasons including embarrassment, not understanding the legal definition of rape and not wanting to label the perpetrator as a rapist. The report also found that more than half of respondents were unsure if their experiences would be considered rape.