Editor’s Note: This is a guest commentary. The opinions do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board.

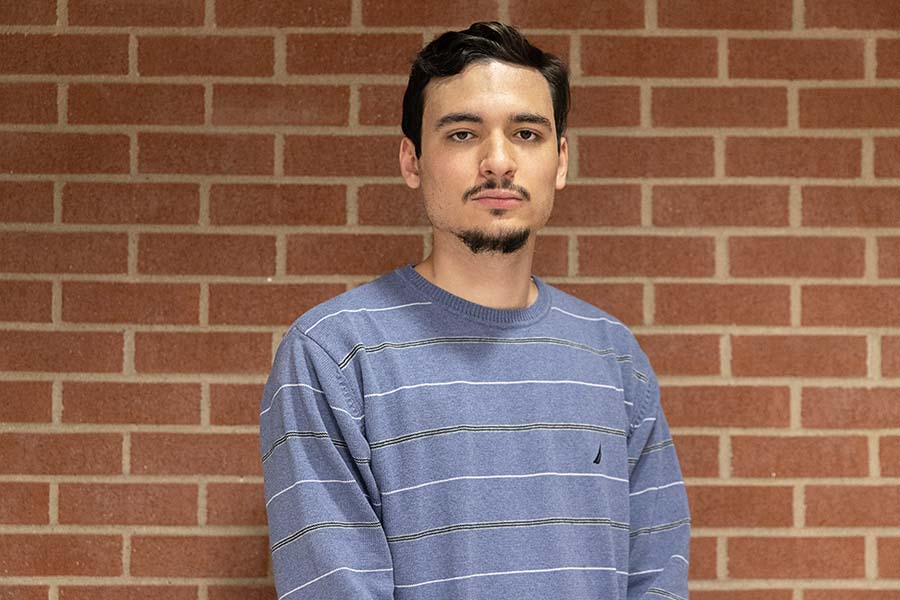

My undergraduate class, Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in K-12 Schools, conducted a linguistic landscape project this fall. The goal of this project was to enable students to, in the ethos of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, read the word and read the world. Research tells us that people rarely pay much attention to the linguistic landscape around them. Therefore, for this project, students are encouraged to imagine themselves as fish trying to see the water around them.

To complete the project, students explored the Ithaca College campus and around town, taking pictures of artifacts of multilingualism. Upon reconvening, students discussed their findings in collaborative groups and presented them to the class. Students followed these guiding questions as they explored, analyzed and presented: What languages are present on campus and in the community? What are some artifacts of multilingualism I can see? Who are the businesses and community groups that display multilingual signs? Who are the intended audiences of multilingual displays? What languages are missing? Whose voices are missing? Students also reflected on what this project meant to them as future educators or professionals in another field, such as speech-language pathology, occupational therapy or film studies. This commentary reflects the collective knowledge gained from our linguistic landscape project.

We acknowledge that our survey of the campus’s linguistic landscape was not thorough. However, we agreed that there was a disconnect between the college’s monolingual landscape and its population of international students, bilingual students and the general student body who would benefit from exposure to multilingualism.

Around town, we found rich multilingual artifacts. Community organizations such as Open Doors English and Ithaca Welcomes Refugees display multilingual signs in their service and advocacy work. Local restaurants and grocery stores featuring ethnic foods and goods show multilingual menus, aisle signs and bulletin boards. On the bulletin boards at Ren’s Mart, a local Asian market, we saw multilingual information about hair salons, hiring opportunities, ESL classes, driving school, furniture sales, money transfer services and more, representing needs and services in and for Ithaca’s diverse communities. Multilingual signs at Wegmans and Walmart pharmacies feature at least 24 languages, including Arabic, Burmese, Bengali, Farsi, Haitian Creole and Romanian. People in need can simply point to a language to request language access services. The Namgyal Monastery on South Hill shows sacred texts of Tibetan Buddhism. We also noticed the Chinese and English bilingual signage at Ithaca Tompkins International Airport and the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫ’ street signs downtown. These multilingual artifacts signify Ithaca’s diverse international, immigrant and refugee populations, as well as the profound histories of Indigenous peoples who inhabit this land.

On campus, multilingual artifacts are scarce and scattered. We found a Spanish-English bilingual schedule of the Cine Con Cultura 2024 Latin@ American Film Festival. In the Whalen Center for Music, there was a poster for the 2024 International Chinese Vocal Competition. While these posters tended to rotate in and out somewhat frequently, there was a more permanent Japanese-English warning sign in the chemistry department in the Center for Natural Sciences. Chun Li, laboratory instrument coordinator, told us that the sign was in Japanese because the superconducting magnet equipment in the lab was made in Japan.

While there were some examples, much of the signage on campus is in English. We found that the college’s diverse population of multilingualism was not reflected in its methods of communication.

Chicana queer poet, writer and scholar Gloria Anzaldúa said, “I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself.” Advocating for multilingualism at the college is essential for creating a more inclusive campus. Our class invites students to join us and become sociolinguists with a keen eye for multilingualism. So next time you see a bilingual poster or flyer on campus, or a lack thereof, pause and think: In what ways can you advocate for the college to become a more linguistically inclusive space?