When senior Marlowe Padilla was only 5 years old, his parents gave him the important task of ordering food at restaurants for his family of eight. Despite the intimidating task for a child, Padilla’s father would remind him that he is capable of doing it.

This sense of independence, Padilla said, was ingrained in him at a young age and has influenced his mentality growing up and going through school. Now a college senior, Padilla is on the path to becoming the first in his family to graduate college as a first-generation college student.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 50 percent of students at higher education institutions are first-generation. Results from the study said first-generation students are often influenced by their family and background characteristics, such as being more likely to come from low-income families than students who are not first-generation.

At first, freshman Damian Maravola, who also goes by Damiano Malvasio, did not want to attend college due to the promise of high debt. However, he said knowing he is a first-generation college student ultimately motivated him to attend college as a representative of his family name.

“When you’re the first ones, you’re carrying the torch almost. It’s like you’re the one who has to represent all these people,” he said. “You have to take every amount of history that is in your family and in your blood, and you have to make something of it.”

Maravola remembers what his mother always told him: to always focus on school. He said he believes in the idea that his schooling comes first, especially because of the cost.

“Because we’re spending so much time and money on this, to fail would be stupid, and it’s kind of like a disrespect to the family,” he said. “There’s no other option. Success is the option. Failure’s not.”

Since his parents and older siblings were unfamiliar with the U.S. education system, Padilla said it would often be difficult to relate to his parents and ask them for help because of the stark contrast of their educational experiences.

“It was hard for me,” he said. “When I had a problem with school, … that’s where the independence comes from. … I had to figure that out on my own, essentially, because they didn’t even know what I was going through.”

Because Padilla is the first in his family to attend college, he said, while there is a lot of pressure to set an example for his family and future generations to come, he has always kept his family in mind throughout his educational career.

“I’m gonna prove to my parents, I’m gonna show my parents ‘Your money’s not being wasted, and you raised a really good son, hopefully, and I’m using everything that you taught me to better myself and the people around me,’” he said.

First-generation students often feel both external and internal pressure, primarily from their families, to achieve success. Oftentimes, the circumstance of their parents motivates them to further their position by receiving an education, an opportunity their parents were unable to reap the benefits of.

Freshman Julissa Martinez is a first-generation student whose mother grew up in a poor family in the Dominican Republic and was ultimately unable to finish elementary school. Martinez said the hardships her mother experienced and the opportunities she did not have influenced her outlook on education.

“She always tells me it’s important to go to school,” she said. “I think it’s because she never was able to go. She wants me to have the mentality of going and becoming successful because she was never able to [do] that.”

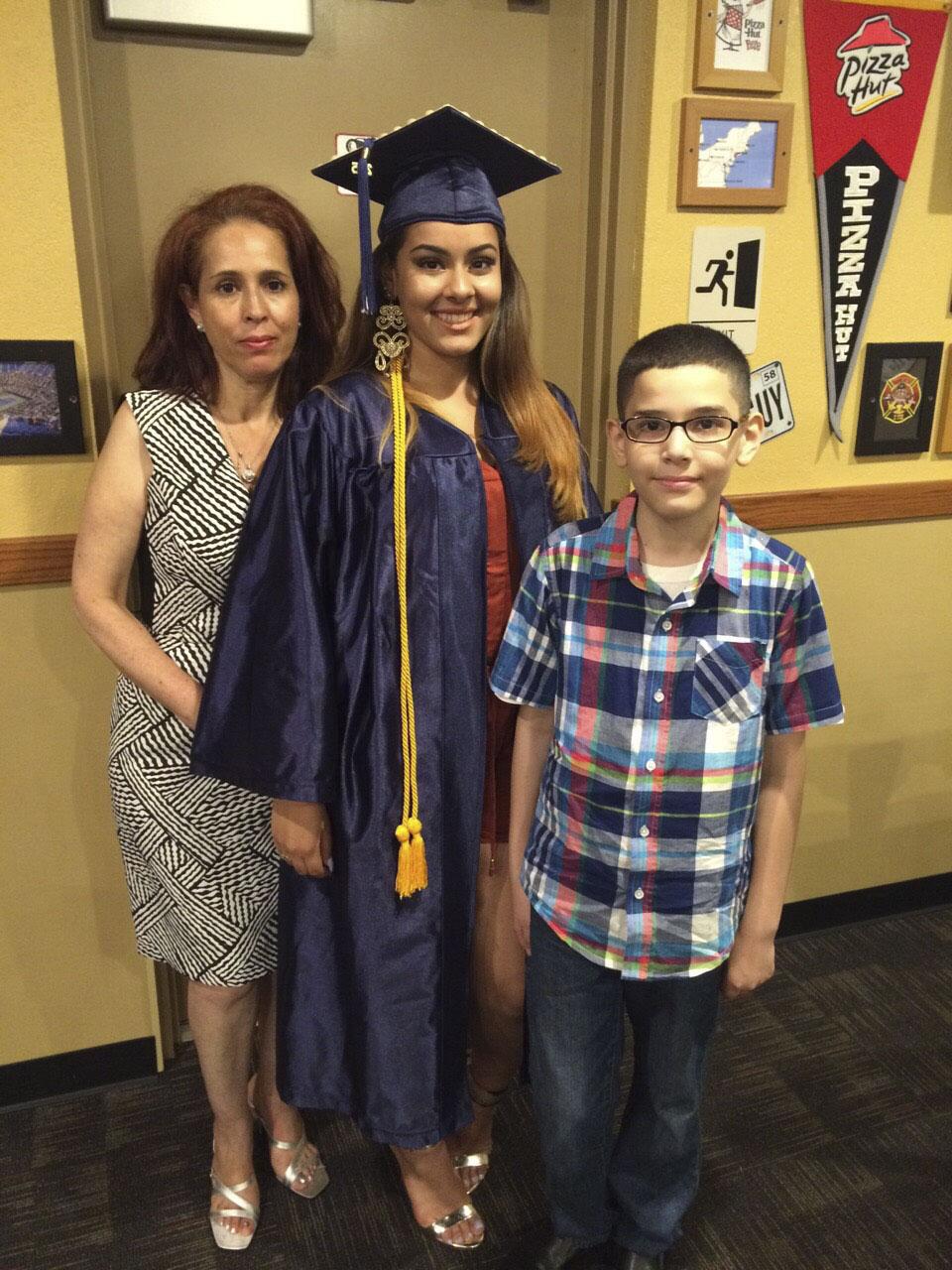

Courtesy of Julissa Martinez.

Due to the lack of the parents’ college education, many first-generation college students also come from low-income families. It can be difficult for first-generation students to access the resources necessary to guide them through their educational career because of financial burdens, such as the inability to afford a tutor. According to the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 46.8 percent of low-income, first-generation college students are dropouts, compared to the 23.3 percent dropout rate of students who are neither low-income nor first-generation.

While many nonprofits exist to assist and meet the needs of first-generation students, most students face the daunting task of taking charge of their education themselves, as was the case for freshman Cindy Prado, raised in Flushing, New York, by a single mother from El Salvador.

Prado said her mother does not speak English very fluently, and therefore Prado had to take responsibility for the college application process.

“I had to do all the financial aid calls to certain colleges, I had to deal with FAFSA myself, [and] I had to do the CSS profile myself,” she said. “She didn’t know how to do it, and I couldn’t blame her for it. I had to basically do all the taxes, so I was in charge. I was kind of being my own parent at that point.”

Retention and graduation rates of first-generation college students tend to be lower than those who are not the first in their family to attend college. Prado said one factor contributing to this statistic could be the inability of parents to offer help to their children in terms of their education.

“It’s really sad that you’re younger, much younger, than them but your education is much higher than theirs, so there’s no one really around you to help you,” she said. “And you have to look for a tutor, but tutors cost money, so then you don’t have money, so you don’t have a tutor … there’s no person to fall back on for support that’s not emotional or mental support.”

Accompanied with the pressures of achieving academic success are the financial strains first-generations must shoulder, as is the experience of freshman Alexa Ubeda. Because she is here on a scholarship, she said it already places pressure on her to maintain her grades in order to keep her scholarship and continue attending Ithaca College.

“I need to keep up my grades. I need to make sure to have my priorities straight so that I don’t lose my scholarship because my parents don’t have a degree and therefore their jobs are not as good, and so they don’t have the money to pay for my education,” she said. “And also I feel like I have that pressure of my financial needs and some people don’t have that pressure — I feel like that’s a privilege.”

Courtesy of Alexa Ubeda

Sally Neal, director of the Center for Academic Advancement at the college, said via email the college does not offer any specific programs for first-generation students so as to not single out this specific group. Instead, she said the college offers several services to provide academic support for any and all students. The college’s Knowledge without Borders Study Abroad Scholarship, however, is preferenced toward first-generation students who are participating in a study abroad program.

The four main departments offering programs to ensure academic success are the Academic Advising Center, Tutoring Services, the Office of State Grants and Student Accessibility Services. Padilla said he credits the Office of Student Engagement and Multicultural Affairs and the Ithaca Achievement Program for helping him succeed throughout his years at the college.

“They help plan success for [African, Latino, Asian and Native American] students, and I think first-generation college students kind of encompass that as well,” he said. “So it’s all about goal setting, where to find certain resources and stuff. So because of that program really, I’ve learned to kind of figure out things on my own but also where to go to find the information that I need.”

At one point during college, Padilla said he was almost unable to return to the college due to financial issues. After being awarded the position of a resident assistant and help from OSEMA and IAP, he was able to return, and said the high cost of receiving a college degree is in and of itself a source of motivation.

“I think there’s just this expectation on me that, you know, college is not cheap. You know, my family has raised me with really good morals and stuff, and it’s all about what I’m doing in school with the things that they’ve taught me, essentially,” he said.

Despite these hardships, many first-generation students harbor the driving motivation to work hard and succeed. Maravola said his loyalty to his family drives him to work hard and be a strong role model for his family, and by greater extension, his community.

“Family is loyal to each other, especially in the Hispanic community. We are extremely loyal to our people,” he said. “So even if I’m not representing just my family, I’m representing Hispanic people and I’m representing all the [people of color], so if one makes it, we all make it.”

Ever since his freshman year, Padilla has remained very involved with OSEMA and the student community at the college. This year he is the senior class president and has also served as an orientation leader, an RA and the president of several student organizations. He has also worked for OSEMA and studied abroad in Sydney, Australia, during the Spring 2015 semester. For all these experiences, Padilla gives credit to being a first-generation student and the mentality ingrained in him from his parents. He said everything he does ties back to his family roots and the motivation to succeed and make them proud.

“My parents came here, like, with the American dream in mind, so I think I kind of like to think of myself as a child born in that kind of mentality,” he said. “I think my parents especially wanted to raise a child here in the U.S., kind of reap the benefits they weren’t able to achieve in the Philippines essentially. So I think I’m, like, what they wanted in life essentially, so I take every single opportunity, and I don’t hesitate, I just take it … I put a lot on my plate every year that I’ve been here, but I think at the end of the day it’s all worth it.”