This article is part of a two-part series on the installation of an artificial turf field at Bertino Field at Butterfield Stadium and its impacts on the campus community. The second part will be in the next edition of The Ithacan.

Despite Ithaca College’s stated commitments to public health, the environment and cutting carbon emissions, the college is building a new artificial football field that will expose athletes to cancer-causing chemicals, pollute ecosystems and increase greenhouse gas emissions, according to multiple scientists The Ithacan spoke to.

On Nov. 29, 2022, the college announced that Monica Bertino Wooden ’81 — whose brother, John Bertino ’80, was a part of the 1979 National Championship football team — had donated $3 million to replace the college’s natural-grass Butterfield Stadium with a new artificial turf. The field, which is in Butterfield Stadium, will also be renamed as Bertino Field.

The donation came after the college’s football team had its best season since 1986, going undefeated in the regular season and reaching the national quarterfinals. In the announcement, the college told the campus community that replacing the artificial turf would have environmental benefits.

“The project is expected to bring positive environmental and economic benefits as well,” the announcement said. “Synthetic turf fields conserve water since irrigation is not needed, and the stormwater runoff is cleaner since it will not include the fertilizers and pesticides required for natural-grass fields.”

However, according to oceanographers, ecologists and environmental policy experts, the life cycle of an artificial turf field has detrimental effects on human health and the environment. These risks are higher than those from natural turf, even when adjusted to take into consideration the fertilizers, pesticides and paint that a natural grass turf requires.

Environmental effects of artificial turf

Sarah-Jeanne Royer is an oceanographer and scholar at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where she specializes in how the degradation of plastics affects the environment. In 2018, Royer co-authored a study on the life cycle of plastic in the environment. The study concluded that polyethylene — the most common type of plastic and the type used for the grass blades of artificial turf — emits greenhouse gasses, ethylene, propylene and methane into the atmosphere as it breaks down. Methane, which is 20 times more powerful at warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, is currently driving 25% of atmospheric warming. Additionally, the production of one ounce of polyethylene releases an ounce of carbon dioxide, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Royer and other scientists concluded that because of its composition and surface area, artificial turf has a distinctly large contribution to climate change in comparison to other plastics. Following the publication of the study, Royer and other scientists called for bans on artificial turf.

“All different types of plastics emit greenhouse gasses when they are exposed to UV [ultraviolet] light,” Royer said. “Synthetic turf is mostly made out of polyethylene and has a huge surface area with all of the [grass] blades. Synthetic turf has a lot more effect on the environment than anything else made of plastic.”

Both Scott Doyle, director of Energy Management and Sustainability, and Susan Bassett ’79, associate vice president and director of Intercollegiate Athletics, said they did not speak to scientists independent of the college or the synthetic turf industry.

“I spoke with our local resources and experts and read the materials too, but I haven’t connected with folks from other institutions,” Doyle said.

Kyla Bennett is the director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and a former wetlands enforcement coordinator for the Environmental Protection Agency. Bennett said that in addition to being a source of greenhouse gas emissions, artificial turf contains many different toxic chemicals that put the health of athletes in danger. Many of these chemicals are not in natural turf.

“There are all sorts of awful chemicals in here,” Bennett said. “There are PAHs [a class of chemicals that occur naturally in fossil fuels] and all sorts of metals, particularly lead. There are volatile organic compounds, carbon black, which is incredibly scary, styrene, [and] all sorts of carcinogens and flame retardants. The blades themselves have very, very toxic chemicals.”

To help hold the blades in place, most artificial turf fields are filled with 100 to 120 tons of crumb rubber, which is made from recycled tires. Bennett said crumb rubber contains manufactured “forever chemicals” like perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (called PFAs) that never break down. PFAs have adverse effects on human health, put athletes at risk of getting cancer and diabetes and interfere with natural hormones.

“PFAs leech off of artificial turf and into water,” Bennett said. “Dozens of examples of artificial turf [have been tested] and PFAs were found in every single one.”

Megan Wolff is a public health historian and the policy director of Beyond Plastics, a group of scientists and policy experts aiming to end plastic pollution. Wolff said the construction of a fake turf compromises the college’s commitment of going carbon neutral by 2050.

“Not only is [building an artificial turf] in contradiction to net zero goals, it is so much worse than you could ever imagine,” Wolff said. “It’s made out of a petrochemical feedstock that will last forever and is infused with chemicals. Every single phase of the lifecycle of plastic grass is an environmental problem.”

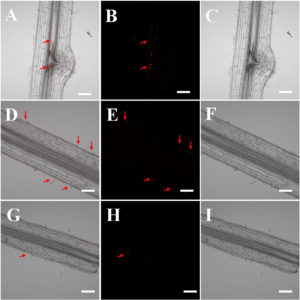

Wolff said artificial turf also creates enormous amounts of microplastics, small pieces of plastic less than 5 mm in length. This is because of rain runoff, the breakdown of the fake grass and pulverization by athletes running on the field. Wolff sent The Ithacan photos of microplastics attached to insects, on a snowflake and within the veins of plants. Wolff said the same type of microplastics seen in the photos are created by artificial turf.

According to research done by Ithaca College’s own Toxicology Lab, around 100 million microplastic particles are in Cayuga Lake. Susan Allen, professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Science, raised concerns similar to those of Wolff, Bennett and Royer in an email to The Ithacan.

“All artificial turf is plastic, which degrades into microplastics — which we know can be problematic in ecosystems, and there is increased evidence of their presence in humans (from ingestion), although the health impacts are not yet very well established,” Allen said in the email.

College’s claims of environmental benefits

In the college’s initial December announcement, it claimed that artificial turf is beneficial to the environment. However, in interviews, multiple officials at the college had conflicting messaging.

In a statement to The Ithacan on behalf of the college’s leadership, Timothy Downs, chief financial officer and vice president for Finance and Administration, said the college had frequent discussions with industry experts before choosing an artificial turf.

“The health and safety of the Ithaca College campus community, along with our visitors and neighbors, is our number one priority,” the statement said. “College leadership is very comfortable with the installation of artificial turf at Butterfield Stadium, which includes the use of an innovative product and a proven installation process that maximizes environmental friendliness.”

In contrast, Ernie McClatchie, associate vice president in the Office of Facilities, said there are risks to artificial turf, including microplastics, but the college believes it has made the safest decision.

“There’s some trade-offs,” McClatchie said. “Artificial turf has negatives to it, natural turf has negatives to it. … We definitely focused on making sure we got the best turf we could get [to make the] switch to artificial turf.”

Bassett said that everything that goes into the care of a grass field — pesticides, watering, mowing, painting and more — makes it less safe for the environment.

“A synthetic surface field is actually more environmentally sustainable,” Bassett said.

Bassett said she knows of the links between PFAs and cancer. However, she said it was important to note that Bertino Field at Butterfield Stadium will not be the first artificial field on campus, and the majority of surfaces athletes play on are synthetic turf as well.

“We are aware of it and obviously concerned about all relevant safety and environmental impact, and we’re confident we can mitigate those risks,” Bassett said. “[But the athletes] have grown up with it and worked on it and competed on it, probably through their whole athletic careers.”

Doyle said that using artificial turf will reduce the college’s Scope 1 carbon emissions — direct emissions from stationary sources like boilers and water heaters. Since artificial turf does not require lawn maintenance, carbon emissions are reduced. However, natural grass fields absorb carbon dioxide and artificial turfs require carbon to be made and have carbon in the blades that gets released into the environment as the blades break down.

“I felt like there were a lot of things that would help us move forward environmentally speaking,” Doyle said. “I have a great deal of concerns about microplastics too. … I think that’s a very valid, real concern about introducing plastics in the environment. But I think in this case we’re striving to manage that as effectively as we can.”

In 2011, Higgins Stadium was installed and is used by the field hockey and lacrosse teams for their regular season, but is also the only surface available for intramural, club or other varsity sports if the weather does not allow practice on one of the natural grass fields. So, Bassett said, a benefit of the synthetic surface is that Butterfield will now be usable for the entire year instead of just the five or six home games the football team plays each season.

“[In inclement weather], we just have a logjam where we’re not able to support the needs and interests of all the programs,” Bassett said. “I absolutely believe that, by doubling our inventory of synthetic surface fields, we’ll actually be able to quadruple our activity.”

Bennett said that while artificial turf does increase play time for athletes, improvements in maintenance for grass fields can increase the play time on natural grass.

“It’s a little bit true that artificial turf can give you more play hours,” Bennett said. “However, that is because the people maintaining grass fields often don’t know how to maintain [natural grass turfs] correctly. If you [maintain] it correctly, the play time is pretty much equivalent.”

Artificial turf industry

The college’s new artificial turf field and the stadium improvements will be serviced by Clark Companies. The manufacturing and direct installation of the turf will be done by Chenango Contracting. Clark Companies is an upstate New York-based sports servicing company that has built artificial and real turf fields at Northeast colleges like Cornell University, Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. In addition, Clark Companies built the artificial surface at MetLife Stadium, home of the New York Jets and New York Giants.

Artificial turf fields are common in collegiate sports and are expanding in numbers. In addition to its preexisting artificial turfs, Cornell recently finished installing a new artificial baseball field.

Chris White ’07 is the marketing manager of Chenango Contracting. White said the college will be using a FieldTurf brand of turf, which contains filtration systems and a concrete curb, both of which White claimed help contain environmentally hazardous components of artificial turf.

“There’s literally no way for sand and rubber to get through the turf itself and get into the base stone, let alone get into the drainage pipe, let alone get kicked out whatever water system you’re connecting to,” White said.

However, Bennett said that while a filter will help prevent larger plastics from entering water systems, it is not possible for filters to remove smaller microplastics, as well as PFAs.

“It might filter out some of the microplastics and bigger macroplastics, but it will not filter out PFAs or PAHs or benzene or any other chemicals,” Bennett said. “There’s no way to just filter that stuff out.”

The artificial turf industry, which was worth $2.7 billion in 2019 and is expected to grow to $3.8 billion by 2025, has pushed the idea that artificial turf is better for the environment. Many artificial turf companies make claims online that artificial turf is good for the environment without citing scientific research, or cite scientists who have worked for the plastics or artificial turf industry. The artificial turf industry is part of the global plastics industry, which was worth $609.1 billion in 2022 and wields major political influence.

“Over and over, in towns across the country, we see the same industry playbook,” Bennett said. “It’s really very frustrating. … Of course, the industry immediately says [to us,] ‘You’re wrong.’ They called me ‘some woman who just did it wrong’ and they refuse to admit that there [are] PFAs in the turf.”

While White said there will be PFAs in the turf that the college receives, he said they were a type of PFA that are safe for humans. However, according to Bennett, there are thousands of different types of PFAs, and most remain untested and the types that have been tested are known to cause cancer. Additionally, the industry, like the college, has made claims that natural grass fields are not environmentally friendly because they require fertilizer, pesticides and irrigation. Most fertilizers used on natural grass fields are made with fossil fuels and contain nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.

James Catella, director of Design and Construction at Clark Companies, said the chemicals used on natural grass are toxic and also an environmental concern.

“Because we build a lot of natural grass fields, we see both sides of the discussion all the time,” Catella said. “It’s not just fertilizers, but for real, natural grass fields … it takes more than fertilizers — it takes fungicides, pesticides, herbicides, a lot of top dressing and overseeding.”

However, Wolff said fossil fuel-free fertilizers that do not contain nitrous oxide are becoming economically feasible, and environmental damage from artificial turf is far larger than that of natural grass. In 2022, the city of Boston banned artificial turfs. Additionally, two proposed bills are in the Connecticut and Massachusetts state legislatures to ban artificial turfs.

Bennett said claims that artificial turf is good for the environment are greenwashing, a form of misinformation that makes something environmentally damaging appear environmentally friendly.

“Have we learned nothing from the tobacco industry, from the formaldehyde industry, from the meat and dairy industry, from [the] oil and gas industry?” Bennett said.

Every scientist The Ithacan interviewed said the college’s goal to be carbon neutral by 2050 is at odds with its announced construction of a plastic turf.

“Plastic grass is the farthest thing from sustainable that you can get, seriously,” Wolff said. “This is the worst thing Ithaca College can do for the environment.”