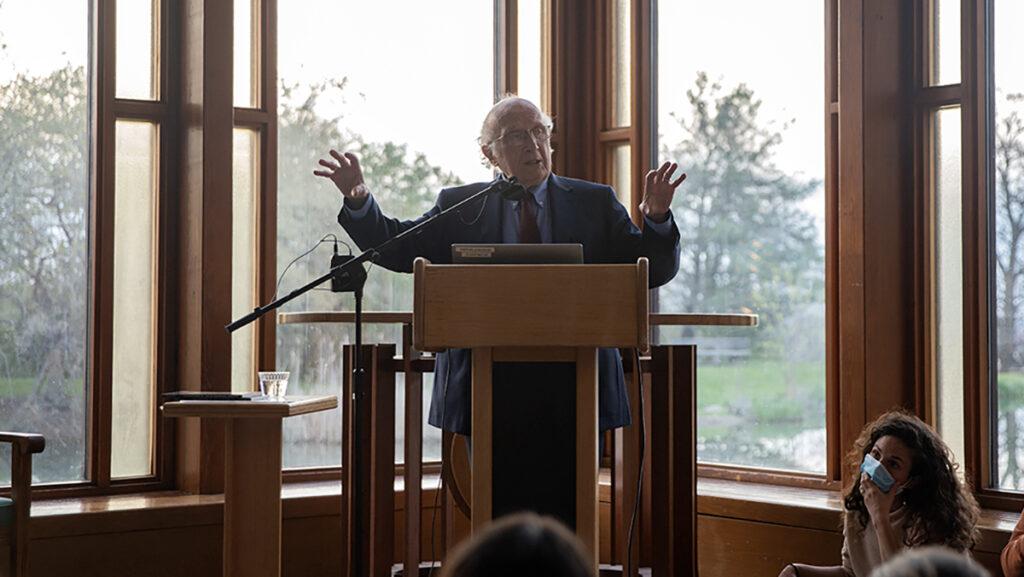

Roald Hoffmann, age 85, is a former Cornell professor, a Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, an Ithaca local and one of the decreasing numbers of Holocaust survivors. Hoffmann was invited to Ithaca College by Hillel at Ithaca College to tell his life story on April 25.

There are under 50,000 Holocaust survivors alive as of 2022, according to a report from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Reports of antisemitism, Holocaust denialism and ignorance have been rising for years and there were eight swastikas found on the college’s campus in 2022. As survivors’ stories fade and fear of censorship grows, Hoffmann said there are many concerns that these stories will not be told.

President La Jerne Cornish introduced Hoffmann and spoke on how important these opportunities are for students to engage with.

“Each year that we have an opportunity to hear from Holocaust survivors like Hoffmann is a blessing and is also an opportunity to bear witness to the legacy of survivors and honor their memories,” Cornish said. “We confirm our commitment to never forget the Holocaust.”

Senior Nora Marcus-Hecht, who is on the Hillel student board, said that although she has heard Hoffmann speak before, bringing his story to Ithaca is very important to her.

“As someone who has grown up in Ithaca, this isn’t the first talk from Dr. Hoffmann I’ve experienced,” Marcus-Hecht said. “Bringing him into our space here at Ithaca College is incredibly meaningful for me.”

Hillel has brought guest speakers to campus before, including Hannah Wechsler, Uriel Abulof, Nizar Farsakh and Eric Cheyfitz.

Hoffmann began by comparing a picture of a war-torn, modern day Mariupol, Ukraine, to a photo from Warsaw, Poland, in 1945. Hoffmann said that looking at pictures of Mariupol gives him a sensory feeling of Warsaw in 1945 and brings back the blurry vision of dust in the air and horrid smells.

“When will we learn?” Hoffmann asked.

Hoffmann was born 1937 in Zolochiv, Poland, which is now part of Ukraine. When Germany invaded Poland, his family was forced to stay in a labor camp during the beginning of World War II. Hoffmann displayed a map outlining the movement of troops at the start of the war but said he disdains using these maps.

“Those arrows are the movements of thousands of armed people who are killing other people,” Hoffmann said. “It hurts to have the deaths of millions of humans — soldiers or civilians — reduced to the movement of an arrow.”

After bribing their way out of the labor camp in 1942, Hoffmann said his family stayed in the attic of a nearby school house for 15 months. There was a single window where he watched kids his age play during recess. The winter months led to the attic being extremely cold, forcing the family to stay in even more compact storage rooms. When Hoffmann went back to the Zolochiv school house in 2006, he discovered the storage room had been turned into a chemistry classroom.

“The children learning in these rooms didn’t know I was hiding under these floorboards 50 years earlier,” Hoffmann said.

In July 1944, the USSR took control of Zolochiv. This allowed Hoffmann and his mother to move to Karkow, Poland. Hoffmann said his mother then obtained a small amount of extra money to buy a coat. Despite being lower class, Hoffmann said he saw this as being the first step to a return to normalcy for his family.

“We were freed by the forces of evil,” Hoffmann said. “The coat was not a frivolous thing; it was a sign of being human again.”

It was in Krakow that Hoffmann’s mother was given the news of her husband’s death, which had gone unconfirmed for months.

“I didn’t know what I was crying about, but I cried because my mother was crying,” Hoffmann said. “It was an extremely difficult time, but life had to go on.”

Hoffmann spoke about the family that sheltered them, the Dyuks, and how important it is that he keeps in contact with them. He said that in the 1960s, when his family was staying in New York City, a letter came from the Dyuks requesting embroidery thread, something that USSR-occupied Ukraine had at the time, but was not the best quality because of the damaged economy post-war. When visiting with the Dyuks 40 years later, Hoffmann said he discovered the embroidery thread sewn into a cloth still on display in their home. He said he recognizes how important something this small can be toward recovering.

“It’s almost like an oath,” Hoffmann said. “It’s an object that stands for much more than it was and what it is.”

Hoffmann transitioned into discussing his views on survival and the future of education about the Holocaust. He focused on the semantics of survival, the romanization of this term over time and what it means to be a survivor.

“You should not think that because someone has survived that they are somehow better,” Hoffmann said. “One should not feel guilty about surviving. … Survival is a sign that we are here.”

There have been many attempts to catalog survivors’ stories through websites and detailed biographies. Hoffmann said that not only stories of the horrid actions must be told but also stories of generosity.

“There is something special about remembering the good actions, as what the Dyuks did for us,” Hoffmann said. “Those actions resonate with something deep within us that human beings are good. … Who will speak for those who did not survive and who had such generosity?”