The Ithaca College Board of Trustees announced that it has approved changes to the cost of attendance for the 2023–24 academic year, including an increase to the cost of tuition and housing.

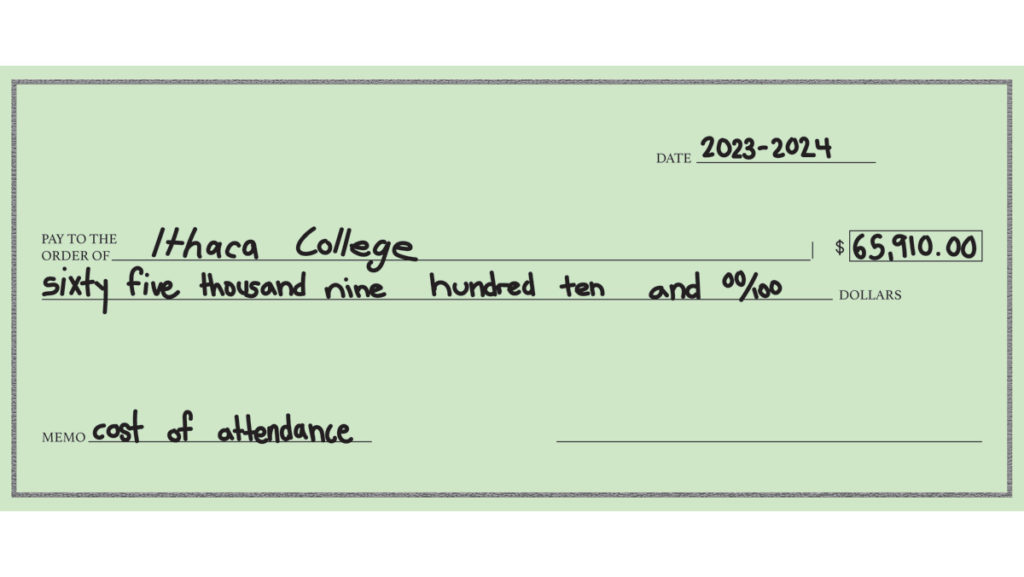

In a Nov. 21 Intercom post, David Lissy ’87, chair of the board of trustees, and James Nolan ’77, vice chair of the board of trustees, said that for full-time undergraduate students who live on campus, the cost of attendance will be increasing by 2.89%, for a total cost of of $65,910. For the 2022–23 academic year, the cost of attendance was $64,060, which was a 2.68% increase from $62,457 in 2021–22. In 2020–21, the cost of attendance was $62,457 and in 2019–20, the cost was $60,845.

Included in the increase is a 3.65% increase in tuition, which is rising to $49,880 from $48,126 for the 2022–23 academic year. Tuition for most graduate programs will also increase by 3.65%. From 2019 through 2021, the cost of tuition increased by 2.95% each academic year.

According to Forbes, the average tuition prices for private colleges have doubled over the past 30 years, totaling to an annual increase of 3.2% on average.

For the 2023–24 academic year, there is a 1% increase for room — $9,160 — and no increase in board — $6,870. The $75 public health fee has also been eliminated.

“The modest increase for returning students is in line with the Four-Year Financial Forecast first introduced for this year’s incoming class, which set an annual cap of 2.9% on their direct cost increases for each of their four years at the college,” the post stated. “The decision has been made to include current sophomores and juniors by applying this same direct cost cap during their respective junior and senior years at the college.”

Following the implementation of the Four-Year Financial Forecast — a walkthrough of the costs of all four years of attendance for incoming students — for the Class of 2026, each incoming class will be assigned a direct cost cap, meaning that the maximum percentage the cost could increase for their four years will be set prior to their arrival.

Shana Gore, executive director of Student Financial Services, said that, in theory, there could be four different caps for each of the four class years. Gore said that because of the increases in costs for everything as a result of inflation, the college wanted to work to implement the Four-Year Financial Forecast.

“There’s always going to be a cost with higher education,” Gore said. “And we can always make that less. But it’s just important to make sure that students and parents understand what it is and can plan accordingly. And that we are laying things out so that it’s clear and that there’s not any hidden information, or any last minute surprises for students and families.”

The post also stated that the college has decided on the costs for the Class of 2027. The total direct cost for the first year will be $66,540 and the cost increases are set at a maximum of 3.5% each academic year.

Tim Downs, vice president of Finance and Administration and chief financial officer, said there are many factors that go into calculating the maximum cost increase.

“The main factors considered are based on the costs needed to operate the institution,” Downs said via email. “In years, like the last one, where the costs for labor, services and supplies have increased significantly, the cap will be set higher. The benefit of the cap is if we set it higher for a particular incoming class because of the current conditions, but circumstances change; we can always set actual rates lower than the cap.”

According to the post, about 93% of students receive some form of financial aid directly from the college, which adds up to $117 million. Gore said students could receive more aid each year when tuition increases, but it is entirely dependent on the student’s situation and need, as well as where they are receiving the aid from.

Sophomore Ainsley Perkins said she thought the college was not the best in terms of having financial stability. She said she would be receiving more financial aid if she chose to go to an in-state college in her home state of Massachusetts.

“I chose this school for the connections and for believing it would be a good school to come to,” Perkins said. “I also have been very honestly looking at transferring, with price raises, with closing down parts of the school and making it all smaller. … The school has to acknowledge there are a lot of people from Massachusetts here. A lot of us could get it cheaper outside of here, especially with the price raises.”

Junior Henry Vierschilling said he thought the increases in the cost of attendance were disappointing and a sign that the college is still struggling through the COVID-19 pandemic — noting faculty cuts made as a part of the Academic Program Prioritization process as an example. The cost of tuition and budget cuts has been a frequent concern for members of the campus community.

“I had a cousin who was interested or at least potentially interested in applying to the college and I told them … if you had three or four years for the school to recover, get on its feet, I would say go for it,” Vierschilling said. “But this school is so clearly in a state of tumultuousness, that it does not inspire confidence in its students, and to raise prices, raise tuition and housing is, I would say, offensive. I think there needs to be stronger justification than what’s in that [post].”

Staff writer Noa Ran-Ressler contributed reporting to this story.