Across Ithaca College, there are limited course offerings as a result of program and faculty cuts made during the 2020–21 academic year. These changes are one reason curricular revisions across the college are underway.

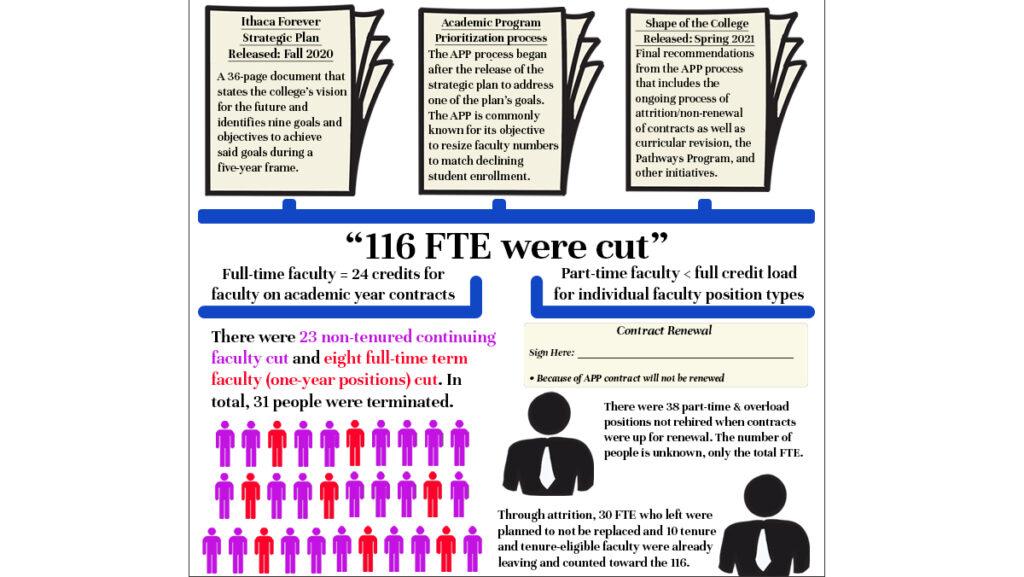

In October 2020, La Jerne Cornish, then-provost and senior vice president for academic affairs and current president of the college, announced that the college planned to cut approximately 130 full-time equivalent faculty members because of a need to “resize the college” after years of declining enrollment. Every academic program at the college was reviewed by the Academic Program Prioritization Implementation Committee as part of the Academic Program Prioritization process. Ultimately, five graduate and 17 undergraduate degree programs as well as three departments across the college were discontinued or suspended because of the APP plan. Additionally, 116 full-time equivalent faculty positions were affected by the cuts, achieved through attrition — voluntary retirements, departures or the non-renewal of contracts. The cuts led to widespread criticism by faculty and students alike, including those affecting the former School of Music, now Center for Music at the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance.

Junior Evie Morse is a music education major and said the cuts have made it more difficult to register for secondary-instrument courses required for her degree program.

“I think it’s been hard on the students for registration,” Morse said. “It’s almost impossible to get into a class now because instead of five sections, there’s maybe two now and it’s really difficult.”

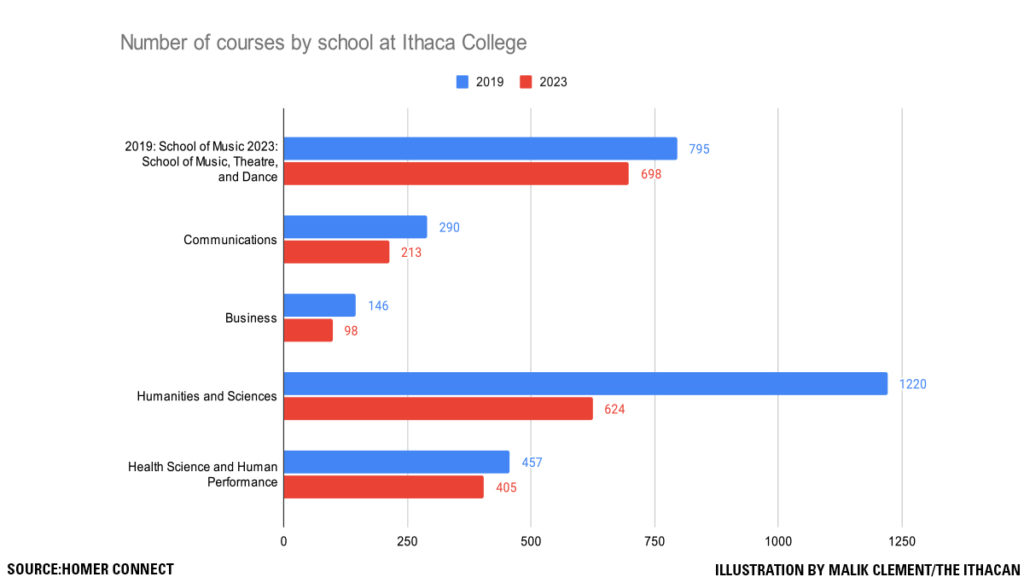

According to Homerconnect, broken up among different schools in Spring 2019, there were 795 courses offered in the School of Music, Theatre and Dance; 290 in the Roy H. Park School of Communications; 146 in the School of Business; 1,220 in the School of Humanities and Sciences; and 457 in the School of Health Science and Human Performance. In Spring 2023, there are now 698 courses in the School of Music, Theatre and Dance, 213 in Park, 98 in the School of Business, 624 in H&S and 405 in HSHP. The decrease in courses in H&S appears significant but many theatre and dance courses were moved from H&S to the new School of Music, Theatre and Dance during the merger.

In criticism of the cuts, faculty shared concern about a rise in workload, and reduced offerings at the college — concerns that appear to have come to fruition, with a pianist shortage in Fall 2022 affecting the Center for Music, and now a continued lack of course offerings impacting the student body across the college.

Under the current music education curriculum, students are required to take secondary-instrument courses. Deborah Martin, professor and chair of the Department of Music Performance, said via email that prior to the APP, most secondary-instrument courses were run by graduate students, and with the suspension of the music graduate programs, there are no longer graduate students to teach secondary courses, causing a chain reaction. Performance faculty, with more limited time, must now teach secondary courses, and because of their limited time and numbers, fewer sections can be offered.

Martin said via email that the lack of graduate students has not only added to faculty workload, but made it difficult to predict how many courses can be offered in future semesters. During the pandemic, the college incentivized retirements that further complicated staffing. Martin said via email that now the Center for Music has to rely more on full-time term lines, better known as one-year contracted professors to fill in the gaps.

“COVID and the mass exodus [of faculty] forced us to rely more heavily on the full-time term, one-year line, ” Martin said. “We were forced to use them for more than 1 year while we waited to see if searches were approved.”

Martin acknowledged the difficulty of having so many professors on a one-year contract in the department.

“We are working each year to eliminate those lines (which we had to add suddenly when so many people left) because they don’t serve us well in the capacity of longevity and continuity,” Martin said in the email.

The rise in faculty workload is felt outside of the Center for Music. According to the Office of Analytics and Institutional Research, in Fall 2019 there were 708 faculty total and in Fall 2022 there were 532 faculty. In Fall 2019 there were 6,266 students enrolled and in Fall 2022 there were 5,054 students enrolled. While the decrease in faculty is part of the APP plan to balance the number of faculty with declining enrollment, faculty and students feel strained.

Ellen Staurowsky, professor in the Department of Media Arts, Sciences and Studies, said she had to step down as the chair of the Faculty Council because of her workload.

“I did that chair role as an overload,” Staurowsky said.“I was already maxed out in the fall, and then moving into the spring with this almost tripling of enrollment in one [of my courses] along with the fact I was teaching four courses, I literally just ran out of time in the day.”

Despite faculty members taking on more responsibilities to make up for the decrease in faculty, there is still a shortage of course offerings at the college.

The shortage of course offerings is one of the reasons many departments across the college are shifting from a three to four-credit model; students will take fewer courses for more credit, a reasoning Staurowsky does not fully agree with because of concerns about quality.

“Usually, curricular decisions are made on the basis of what is the best curriculum to serve the students,” Staurowsky said. “We are making decisions based on the fact that we just don’t have enough personnel to deliver the courses.”

Dan Breen, associate professor in the department of Literatures in English, said that with the move to a four-credit model, faculty must revise curriculum. He said many departments in the School of H&S will be more limited in the variety of courses and opportunities they can offer, including research projects and independent studies because of the changes.

“In Humanities and Sciences especially, the workload has generally increased because a number of departments have had to redesign their curricula since they no longer have enough faculty to deliver curricula as they existed,” Breen said via email. “Faculty retention is, not surprisingly, struggling; in addition to the faculty members whose contracts weren’t renewed as a result of APP, a number of other faculty have left the college voluntarily.”

Juan Arroyo, assistant professor in the Department of Politics, said that by shifting to a four-credit model, students will need to take fewer courses, reducing the number of sections needed.

Arroyo said that under the new four-credit model, the department of politics can no longer offer as many niche courses outside of the standard sequence, which he said also give him concerns about recruiting and retaining students to avoid losing them to colleges with a lower total cost of attendance.

“As professors, we had some margin for creating niche kinds of courses, interesting courses, that might not be mainstream and created the personality of our politics department at IC,” Arroyo said. “So if we’re teaching fewer courses [under the new model] that gives us less freedom to teach other things outside of the bread and butter courses.

In May 2021, the college also announced the closure of the Academic Advising Center less than a decade after it was created, with advising responsibilities transferred to faculty advisors, something Morse said only made things more difficult.

“A lot of studio professors are forced to be student advisors and they don’t know much about scheduling at all because it’s just really not their job,” Morse said. “I mean they’re here to teach an instrument, not to sit you down and write out your schedule.”

First-year student Olivia Malok is an occupational therapy major and said the lack of course offerings has added to the stress of registration, especially for first-year students like herself.

“This is all new to me and I think the fact that the college is changing made it difficult,” Malok said. “I got up at the crack of dawn to get into these classes, I didn’t get into a lot of them because I just couldn’t, like there was only one class available.”

Malok shared those concerns about advising, noting that while her faculty advisor has been helpful, the Department Occupational Therapy has not been as useful or communicative about the issue.

“I haven’t necessarily heard anything from [OT] regarding registration for classes,” Malok said. “They kind of just brush it off a little bit, like ‘oh, well, it’s fine’ ‘You’ll still graduate in five years like we’ll figure it out’. I don’t think that they see it as much of an issue.

Melanie Stein, provost and senior vice president, said departments are creating teach-out plans to support students through the transition, and that the college plans to improve communication to alleviate student anxiety.

Martin acknowledged the challenges of changing the curriculum and supporting students through the transitions. She said in her email that the new curriculum is designed without graduate programs in mind to help alleviate issues students are facing currently.

“I think the new curriculum is better and it certainly needed to be updated as we had not made significant changes in 30+ years,” Martin said via email. “Changing curriculum is HARD, and sometimes there needs to be a catastrophic event to get the ball rolling.”

Editors note: Information about student enrollment and how the creation of the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance impacted course data was added for clarity.