At the All-College Gathering on Aug. 23, Ithaca College President Shirley M. Collado announced that the college’s carbon footprint is projected to drop by 45 percent this academic year. This decrease in overall carbon output is part of the college’s previous pledge to be completely carbon neutral by the year 2050.

Carbon neutrality is achieved when an institution’s net carbon emissions are equal to zero, meaning the college has balanced their emitted carbon emissions with their efforts to curb, or offset, emissions. A college’s carbon footprint and carbon output refer to the total amount of carbon emissions the college has emitted.

Greg Lischke, director of the Office of Energy Management and Sustainability, said approximately 30 percent of this reduction came from the transition to Green-e certified energy that was made in February 2018. Another 10 percent of the reduction comes from the college’s solar panel farm, which was constructed in 2016. Additional reductions are expected due to continued boiler replacement in coordination with the college’s deferred maintenance program later this year.

Currently, the Job Hall boiler heats 15 to 20 percent of the campus, Lischke said. It is expected to be completely decommissioned by the spring of 2019. Once the boiler is decommissioned, a newer, more efficient natural gas-powered system will be installed next summer.

“One of the things I’m appreciative of right now is that there is a dialogue going on about, ‘Okay, that old boiler, do we really just want to take the old boiler out, dispose of it and put in two smaller more efficient boilers, or can we figure out a way to get rid of boilers altogether and try to introduce geothermal?’” Lischke said. “We’re not there yet, but we hope to get there.”

Lischke also said the college will be retrocommissioning the Athletics and Events Center. Retrocommissioning is a systematic process that involves analyzing a building’s older and newer systems — like heating, ventilation and cooling systems — and making sure everything is working as it should be. This could reduce carbon emissions because over time, these systems may slowly and subtly shift or drift, which can cause systems to use more energy, therefore being less efficient.

“Unless people complain or unless you look, you may not know you’ve had a drift,” Lischke said. “Say the set point is 70 degrees. That thermostat could be off, so you’re a little hot, but that thermostat still thinks it’s 70. It’s a subtle thing, but when you add all these subtle things up and you look … it’s disruptive, and it’s expensive.”

Lischke said he believes that, as of right now, the college is on track to be carbon neutral by 2050. He said more conversations about the possibility of expediting that date have been scheduled. He said a meeting with the Climate Action Plan Reassessment Team this month will further the discussion. When the team is finished assessing, they will deliver a report to the senior administration.

In 2009, the college’s board of trustees approved a Climate Action Plan that promised to make the college carbon neutral by 2050 with the goal of reducing carbon emissions 25 percent by 2015 and 50 percent by 2025. The 2015 goal was not met, and carbon emissions actually increased. Part of the reason the 2015 goal was not met is that, under former President Tom Rochon from 2008–17, sustainability was not a priority as it was for the Peggy Ryan Williams administration.

The college has implemented several projects to keep this promise — like the Green-e energy switch, the solar farm and consistent upgrades to infrastructure. At a student media conference on Sept. 6, ollado said she will be incorporating sustainable practices for people, finances and the environment into the five-year strategic plan.

William Guerrero, vice president for finance and administration, said he agrees that, from a strictly financial standpoint, the college can be carbon neutral by 2050. He said a lot can happen in 32 years but that he is hopeful.

“It’s a priority,” he said. “It’s a priority for the president. It’s a priority for the senior leadership team. … It’s not going to be easy, but it’s a value of the institution.”

Guerrero said that when looking on a financial level at sustainability projects, it is hard to determine the long-term versus short-term costs. He said that in the long term, switching to sustainable practices is usually cheaper. However, if it is a contract-based switch, like the Green-e energy switch, it is harder to tell the long-term cost. The Green-e energy switch was made in February 2018 and powers all the college’s scope two emissions, which are mainly electricity, using renewable energy from wind farms.

“I would say going forward, it is probably going to be more and more challenging because … when you start installing or upgrading equipment to make things more environmentally friendly, you reach sort of a tipping point where you’ve already hit the best you can,” Guerrero said. “That’s when you start looking for newer technologies.”

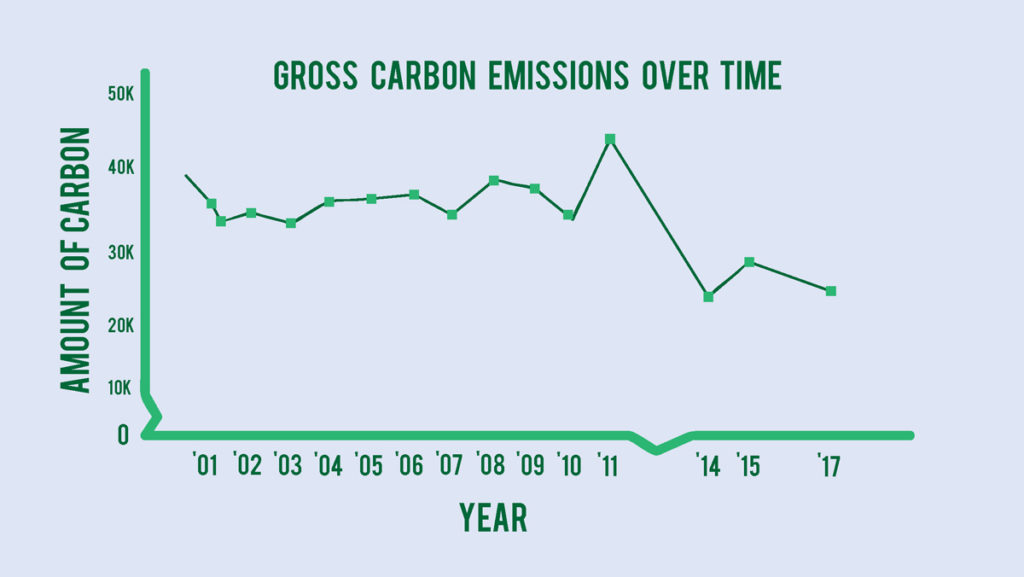

According to Second Nature, the organization the college reports its carbon data to, the college emitted a total gross of 23,673 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCO2e) in 2017.

This number does not include the data from the Green-e certified energy change, which will be completely represented in the 2019 fiscal year report. In the year 2000, the college emitted a total gross of 33,301 MTCO2e. However, there have been years when there have been spikes in carbon output. In 2011, the college emitted a gross of 44,357.1 MTCO2e.

Carleton College, located in Northfield, Minnesota, is a private liberal arts institution that also pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050. In 2017, it reported to emit a gross 23,275.35 MTCO2e compared to a gross 27,278.43 MTCO2e in 2008, the year it started reporting to Second Nature. However, Carleton College enrolled 2,023 undergraduates in 2017 compared to the college’s 5,936 undergraduate enrollment count.

Rebecca Evans, campus sustainability coordinator in the Department of Energy Management and Sustainability, said she also believes the college will be carbon neutral by 2050 but hopes that date will be able to be moved up. She said she hopes to see more big reductions in the future but is unsure of the timeline.

“We have to take chips out of it,” she said. “We’ve gotten all the low hanging fruit, and now we have to get the rest of it.”

Evans said in her opinion, changing people’s behavior will be the hardest part of addressing sustainability on campus. She also said the scope one emissions, which are mainly natural gas-related emissions, will also be very hard to address because the college needs to heat buildings in the fall and winter months. Natural gas is also currently inexpensive.

Moving forward, Lischke said, the scope one emissions will be the hardest to eliminate. He said he has a few theories about how to tackle the issue, such as geothermal and an ambient loop system that would allow older equipment to become more efficient.

Overall, he said he is hopeful that the college will continue to implement more sustainable systems in the future.

“As long as you’re headed in the right direction,” Lischke said.