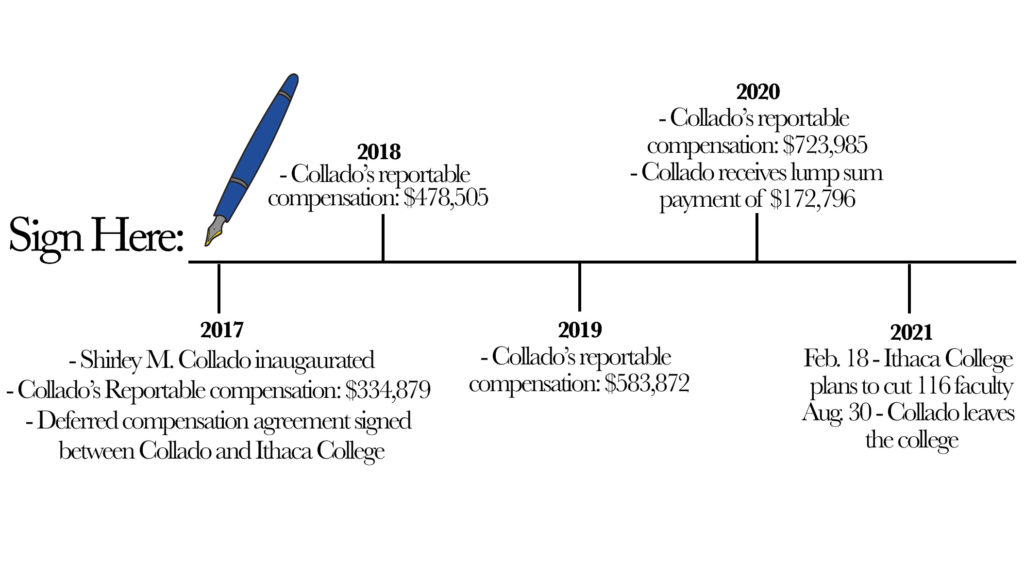

In 2020 — the same year that former Ithaca College President Shirley M. Collado and her administration began the process of eliminating 116 full-time equivalent faculty positions — Collado’s reportable compensation jumped from $583,872 in 2019 to $723,985.

This jump is because of a deferred compensation plan worth $172,796 that matured in 2020 and brought her reportable compensation to the highest amount disclosed from her four-year tenure from 2017 to 2021. Throughout 2020, the college’s leadership furloughed hundreds of employees and began pushing for faculty cuts. Concurrently, they told students, faculty, The Ithacan and alumni that they were cutting their own compensation. While these cuts appear to have occurred, the college’s leaders kept their six–figure incomes intact during the height of the pandemic.

This information comes from the college’s 2020–21 Form 990, which was released in July 2022. The Form 990 is a federal tax form that all nonprofits are required to file to the IRS each fiscal year. The most recent Form 990 reports the compensation of key employees and officers during the 2020 calendar year — Jan. 1, 2020, to Dec. 30, 2020.

Collado’s base compensation

The reportable compensation of $723,985 that Collado received during the 2020 calendar year comes from multiple places — Collado’s base compensation, which is decided by the college’s Board of Trustees, and her other reportable compensation. Base compensation is the amount that an employee receives in their paycheck, not including most benefits or accounting for taxes, as defined by the IRS. For the 2020 calendar year, Collado’s reported base compensation was $487,303, a slight decrease from her $487,853 base compensation in the 2019 calendar year, as listed in the 2019–20 Form 990. Other reportable compensation is the amount given to employees from benefits like retirement compensation, vacation pay and deferred compensation plans.

Financial Services Controller Sean Kanazawich is one of the authors of the college’s Form 990. Kanazawich said the base compensation listed on Form 990 does not include pre-tax deductions like medical and dental benefits. As a result, Kanazawich said, contractual base compensation for the college’s executives cannot be found without access to the college’s contracts with employees, which are private.

The college has repeatedly denied The Ithacan’s requests to view any private compensation information. Additionally, in November 2022, Collado denied a request for The Ithacan to view her contract with the college. In January 2023, Collado did not respond to a request for comment.

David Maley, director of Public Relations, said via email that Collado’s cut occurred but does not appear on the Form 990 in full because compensation adjustments at the college occur July 1. The 2021–22 Form 990, which will be released in July 2023, will show Collado’s compensation through January 2021 to August 2021.

“As announced previously by former President Collado, she and her entire Senior Leadership Team [SLT] had elected to reduce their base compensation for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2021,” Maley said via email. “A portion of that reduction shows up in this filing, though the full reduction is not indicated because calendar year compensation is reported on Form 990, whereas the college operates on a fiscal year.”

Collado’s deferred compensation plan

Collado’s other reportable compensation in the 2020 calendar year was $236,682. This amount is $140,663 more than her other reportable compensation in the 2019 calendar year, which was $96,019.

The deferred compensation plan that Collado had was paid out in the form of a $172,796 lump sum payment, as listed on Schedule J, Part III of the 2020–21 Form 990. Lump sum payments are a sum of money that is paid in one single payment rather than multiple payments.

Deferred compensation plans are incentives for highly compensated executives that withhold pay from the executive until a certain date of maturity. Under a deferred compensation plan, money is set aside by the employer each year until the date of maturity agreed upon in the plan’s contract. On that date, the plan vests and is paid out to the employee in the form of a lump sum payment, meaning the money legally becomes the employee’s all at once.

Saranna Thornton, Elliott Professor of Economics and Business at Hampden-Sydney College, is a specialist in labor economics. Thornton said via email that deferred compensation plans can be renegotiated, meaning that Collado and the Board of Trustees could have cut or reduced the size of Collado’s deferred compensation plan before it was paid out.

“Most elements of a college president’s compensation agreement can be renegotiated at any time,” Thornton said via email. “If both parties (the Board of Trustees and the President) are open to renegotiate it would not be precluded.”

The type of deferred compensation plan that Collado received was a 457(f) plan account for retirement, according to the Form 990. These accounts are only offered for highly paid executives and have no pay cap. Retirement plan accounts that are available for faculty are called 403(b) plan accounts and have an annual limit by the IRS. As of 2023, the IRS’ limit is $22,500.

James H. Finkelstein, professor emeritus of public policy at George Mason University, has spent two decades studying contracts that college presidents receive. Finkelstein said deferred compensation agreements were created in the private sector to retain highly paid executives. Over time, as pay for university presidents has risen, universities co-opted deferred compensation agreements for presidents.

“[Deferred compensation agreements] are a way of sort of hiding the compensation a president receives until some point in the future,” Finkelstein said. “That way staff, faculty and students don’t get upset every year that their presidents are making all this money. They get upset once when it’s paid out.”

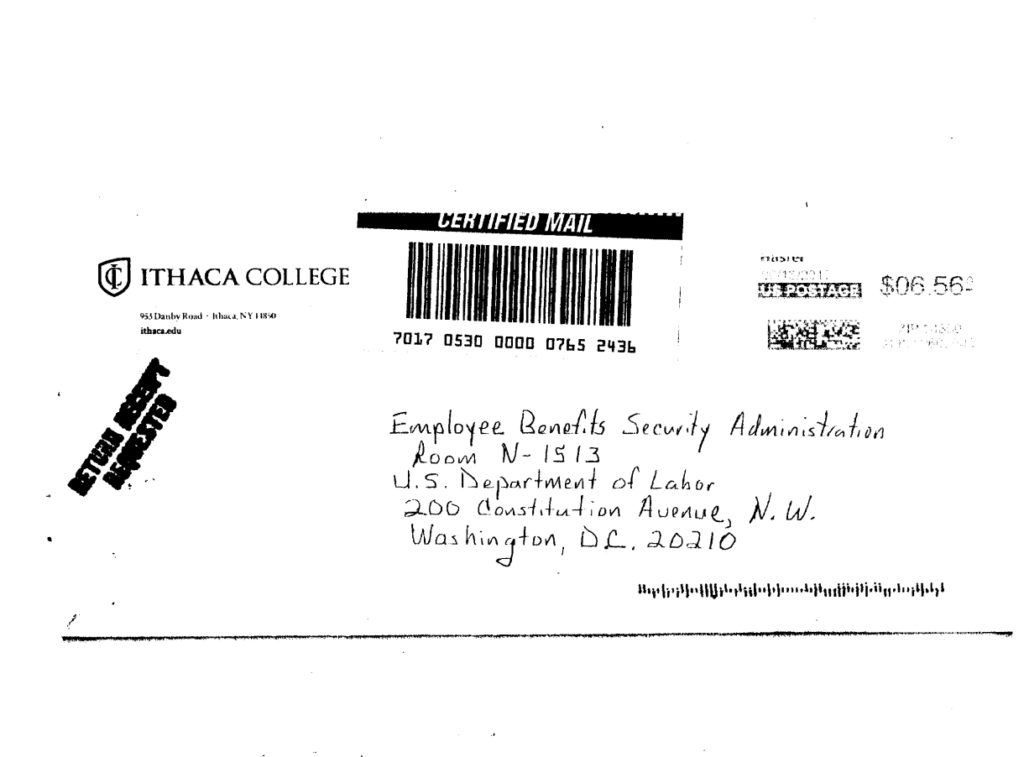

Deferred compensation plans are common among higher education institutions. The two presidents who served prior to Collado — Tom Rochon and Peggy Ryan Williams — both had deferred compensation agreements, according to forms sent to the United States Department of Labor by the college.

A form submitted by the college’s Office of Finance and Administration to the United States Department of Labor shows that Collado entered into a deferred compensation agreement with the college Feb. 22, 2017, the same day that she was announced as the new president of Ithaca College.

Deferred compensation agreement form:

The deferred compensation agreement vested in 2020, the year that the COVID-19 pandemic closed down the college’s campus until Spring 2021. Regardless of when in 2020 the lump sum payment vested, the college was already in a financial crisis. In January 2020, Collado announced oncoming changes that would be “uncomfortable.” The crisis began with a slow decline in student enrollment in the years leading up to the pandemic and was deepened when the college sent students home in March 2020. By August 2020, the college announced an $8 million deficit. At the end of 2020, Collado’s administration announced that 130 full-time faculty members would be cut from the college. Protests on campus followed the announcement.

Compensation of other college leadership

The college’s administration only stated that SLT members were taking salary cuts and refused to disclose the size of the cut that Collado and the SLT members were receiving. During this time period, other college presidents announced the size of their pay cuts, like Cornell University President Martha Pollack, who announced a 20% salary cut after the COVID-19 pandemic caused Cornell’s revenues to decline. Ithaca College’s administration’s decision to shield the size of their salary cuts from the public was criticized by members of the campus community as showing a lack of transparency.

Then-provost La Jerne Cornish, who became interim president after Collado left the college in July 2021 and was officially named president in March 2022, saw her base compensation fall from $243,743 to $237,498 between the 2019–20 and 2020–21 Form 990s. Currently, Cornish’s compensation as president is unknown and when asked by The Ithacan in a Dec. 2021 interview, Cornish declined to say and told The Ithacan to refer to the 2021–22 Form 990, which will be released in July 2023. Cornish’s compensation in 2022, her first full year as president, will be revealed in July 2024, following the release of the 2022–23 Form 990, which will account for the 2022 calendar year.

Fae Dremock, former assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Studies, had her job cut during the layoffs. Dremock said that when she was hired in 2014, she made about $58,000 per year and at the time of the cuts, she was making about $62,000 a year while fighting to keep students at the college.

“We worked hard to sustain the students [during the pandemic] and we were assuming that the administration was working equally hard to sustain us and to take care of the institution,” Dremock said. “To find out that in looking at salaries [that] there was no attempt at that? … It’s unethical. It’s a betrayal of trust. It’s horrific. I could have taken all that I am and all that I have become to reach my students and teach my students about the crisis we face in climate, [but] my career, my doing that is over.”

Kellie Swensen ’22 was a leader of Open the Books, a coalition of students, faculty and alumni who have been calling for increased financial transparency from the college. Swensen said the most recent Form 990 confirms that many of the concerns that Open the Books had raised ended up being true, particularly in regard to Collado’s reportable compensation of $723,985.

“I’ll probably never see that much money in my life,” Swensen said. “I can’t even fathom how much that is. I think when we get into all these conversations about numbers, I really need to stop and take a minute to actually think about how much that is.”

In March 2021, Thomas Pfaff, professor and chair of the Department of Mathematics, wrote a commentary for The Ithacan in which he stated that the decision to keep the size of the cuts quiet allowed for “speculation that the pay cut was little to nothing.” Pfaff said he believes that what he said in the March 2021 commentary holds true.

“There’s nothing to be gained by not saying what they took as a paid cut unless it wasn’t much of a pay cut,” Pfaff said. “Now that it is out, it looks like Shirley Collado’s base pay went down … a little. … I don’t know why they would do that. I mean, given her salary, it’s not like [this] pay cut would have had her having challenges paying bills.”

Between the 2019–20 and the 2020–21 Form 990, the compensation of other SLT members and top college executives either fell, rose or were not listed.

The compensation of SLT members Odalys M. Diaz Piñeiro, chief of staff and secretary to the Board of Trustees; Timothy Downs, vice president for Finance and Administration; and Bonnie Prunty, vice president of Student Affairs and Campus Life, are not listed on the 2020–21 Form 990. Both Piñeiro and Downs are not listed as they joined the college in April 2020, and August 2021, respectively.

The compensation of Laurie Koehler, vice president for Marketing and Enrollment Strategy, and Melanie Stein, provost and senior vice president, are only listed in the 2020–21 Form 990 and cannot be compared to the 2019–20 Form 990. Koehler and Stein’s compensation in the 2020 calendar year was $234,453 and $198,257, respectively. Nancy Pringle, retired vice president, secretary and legal counsel to the Board of Trustees, was compensated $141,534 in the 2019 calendar year. Pringle retired from the college in May 2019. However, her compensation was not listed in the 2020–21 Form 990.

The reportable compensation of SLT member David Weil, chief information officer, rose from $178,193 in the 2019 calendar year to $179,892 in the 2020 calendar year.

High presidential compensation is not new to the college, or higher education in general. According to the 2015–16 Form 990, Rochon’s reportable compensation for the 2015 calendar year was $941,575. For the 2020–21 academic year, the median salary for a private college president was $387,446, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Other benefits

Aside from Collado’s deferred compensation plan, the other reportable compensation section of the Form 990 lists $32,601 that was used for housing, a cleaning person and a leased vehicle. To cover taxes on this income, the college gave Collado a gross-up payment — additional money given to employees to offset taxes — of $31,285, according to the 2020 Form 990. In years prior to 2020, Collado had also received these benefits. The Form 990 also shows that the college contributed $61,500 to a Section 457(F) Supplemental Non-Qualified Retirement Plan that Collado had.

Ithaca College now costs $64,060 to attend each year, and the college is financed almost entirely by student tuition revenue. As tuition at the college continues to rise, students at the college get pushed deeper and deeper into debt. Additionally, compensation data collected by the Chronicle of Higher Education shows that from 2003 to 2020, the average salary of professors at the college is $82,590, lower than the national average of $87,359. Some professors, like Dremock, get paid much lower. When adjusted for inflation, the average salary of professors at the college has remained stagnant for those 15 years.

Additionally, Swensen believes the size of the cuts that Collado and the SLT took were not proportionate to the scale of loss that professors who lost their jobs have experienced.

“If we’re talking about professors — yes, they need money to survive,” Swensen said. “But a lot of professors are there because it gives them some sort of deeper sense of purpose. That kind of loss isn’t as tangible, that loss doesn’t come in dollars and cents.”

Dremock said the college should implement regulation on the salaries of its presidents for the future. While uncommon, regulations over presidential salaries for colleges and universities do exist. In Virginia, there is a maximum amount of state funds that can be used for presidential salaries at Virginia state schools, according to Finkelstein. Some private colleges, such as Red Deer Polytechnic in Canada, have imposed caps on the amount that their presidents can make.

“In the future, let’s decide that the person who runs the college can only make X percent more than faculty,” Dremock said. “Let’s build a reasonable hierarchy for salaries but make it so that it’s a human version; so that the people who work here care about the school and the students [and that] they don’t care about making their career and moving on.”

Correction: A previous version of this article said “In 2020 — the same year that former Ithaca College President Shirley M. Collado and her administration began the process of eliminating 116 members…” which has been corrected to say “In 2020 — the same year that former Ithaca College President Shirley M. Collado and her administration began the process of eliminating 116 full-time equivalent faculty positions…”